Related articles: Managing cardiac symptoms, Health maintenance with Olmesartan

Table of Contents

Cardiovascular diseases

Heart disease or cardiovascular diseases is the class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels (arteries and veins). While the term technically refers to any disease that affects the cardiovascular system, it is usually used to refer to those related to arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

Macrophages are central to atherogenesis because they regulate cholesterol traffic and inflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue. in the arterial wall.

Excess 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 exacerbates tubulointerstitial injury in mice by modulating macrophage phenotype. 1)

According to the Marshall PathogenesisA description for how chronic inflammatory diseases originate and develop., cardiovascular diseases result from the combined effects of communities of microbes that people gradually accumulate over time via the process of successive infectionAn infectious cascade of pathogens in which initial infectious agents slow the immune response and make it easier for subsequent infections to proliferate.. In fact, there is some evidence that arterial plaque may at least be partly composed of biofilm A structured community of microorganisms encapsulated within a self-developed protective matrix and living together., a community of diverse microbes that work together.

While many more pathogens will likely be identified in patients with cardiovascular diseases, certain easily cultured and readily identifiable microbes have been repeatedly identified in people with such conditions including H. pylori, cytomegalovirus, and Chlamydia pneumoniae.2) 3)

One of the best known links between two different inflammatory diseases – and a prototypical illustration of successive infection – is the relationship between cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke, and periodontal disease.

OlmesartanMedication taken regularly by patients on the Marshall Protocol for its ability to activate the Vitamin D Receptor. Also known by the trade name Benicar. , the most essential component of the Marshall ProtocolA curative medical treatment for chronic inflammatory disease. Based on the Marshall Pathogenesis., has several benefits for patients with cardiovascular disease, beyond its role in activating the innate immune system.

Types of cardiovascular disease

- angina – Pain felt in the chest due to insufficient blood supply to the heart, generally as the result of arteriosclerosis of the coronary arteries, usually experienced during exercise or stress

- arrhythmia – A disruption of the regular rhythmic beating of the heart.

- atherosclerosis – A process in which the blood vessels narrow and harden through build-up of plaque in the walls of arteries. Note that atherosclerosis is a more specific type of arteriosclerosis, which refers in a more general sense to the hardening of the arteries.

- congestive heart failure – Develops when the heart’s pumping ability diminishes due to blockages or restriction of blood flow. With heart failure, the weakened heart can’t supply the cells with enough blood. This results in fatigue and shortness of breath.

- coronary artery disease (CAD) – Refers to atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries, which supply the heart muscle with blood.

- heart attack (coronary thrombosis, myocardial infarction [MI]) – When the heart muscle, or myocardium, stops functioning due to loss of blood flow, nutrients, or electric signal. 4)

- high blood pressure (hypertension) – Besides being a measure of poor cardiovascular health, high blood pressure forces your heart and arteries to work harder, and your major organs are affected. You can live for a long time with no signs of high blood pressure, until the whole system begins to collapse under the workload. Reviewed in Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- hypercholesterolemia (hyperlipidemia) – Chronic high levels of cholesterol in the blood. Reviewed in Tests: cholesterol and triglycerides (lipids).

- stroke (cerebrovascular accident) – Strokes occur when blood vessels that carry oxygen and nutrients to the brain are either blocked by a clot (thrombosis or embolism) or burst. Blood (and oxygen) is no longer able to reach the brain, and the brain starts to die. Affects the arteries leading to and within the brain.

Evidence of infectious cause

Immunoinflammatory processes due to chronic infection are thought to be one of the definitive atherogenetic processes.

K. Ayada et al.5)

According to the Marshall Pathogenesis, cardiovascular diseases result from the combined effects of communities of microbes that people gradually accumulate over time via the process of successive infection.

Role of infectious burden in cardiovascular disease

Related articles: Successive infection and variability in disease, Koch's postulates

Chronic and acute infections have been implicated as risk factors that increase the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and other vascular events. The lack of consistency among studies attempting to link exposure to infectious pathogens and cardiovascular disease risk is evidence that a single pathogen is likely not responsible for these diseases. However:

Reconsidering exposure as an “infectious burden” (IB) aligns with our understanding that the totality of pro-inflammatory agents can contribute to atherosclerosis and vascular risk. We define IB as the cumulative life-course exposure to infectious agents that elicit strong inflammatory responses….

Elkind et al.6)

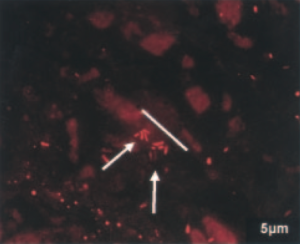

Arterial plaque may contain biofilm

Arterial plaque may contain and/or be caused by biofilm, that is, a community of diverse microbes that work together. Ott et al.'s work which showed a diverse groups of bacterial “signatures” in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary heart disease. Using 16S rDNA sequencing, the team was able to identify over 50 different species including Staphylococcus species, Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Streptococcus species in plaque. The team concluded, “Detection of a broad variety of molecular signatures in all [coronary heart disease] specimens suggests that diverse bacterial colonization may be more important than a single pathogen.”7)

In a commentary following Ott's paper, Katz and Shannon concluded that his work suggested that atherosclerotic plaques are composed of “functional biofilm.” The team noted that the characteristics of a “mature” arterial wall make it well-suited for biofilm formation. These findings further suggest:

A “conspiracy” of bacterial pathogens as opposed to a single infection is involved in atherogenesis, which may help to explain the inefficacy of antibiotics, such as macrolides or fluoroquinolones, in clinical trials.

Joel T. Katz, MD and Richard P. Shannon, MD 8)

Immune cells are abundant in the walls of the arteries even during the initial stages of plaque formation.9) Macrophages have been shown to infiltrate arterial plaque and express a variety of matrix-degrading enzymes that weaken and sometimes break apart the fibrous caps which holds the plaque intact.10) 11) A portion of arterial plaque consists of apoptized (dead) macrophages.

Individual pathogens already implicated in cardiovascular disease

While many more pathogens will likely be identified in patients with cardiovascular diseases, certain easily cultured and readily identifiable microbes have been repeatedly identified in people with such conditions. These include:

- Chlamydia pneumoniae – C. pnuemonia can readily switch between reproductive and latent forms12) – and, as an intracellular gram-negative bacterium, has been shown to infect macrophages responsible for degrading plaque.13) Mycoplasma pneumoniae, another intracellular pathogen, has also been associated with atherosclerosis.14) A number of studies have been conducted to determine the specific association between C. pneumoniae and the development of atherosclerotic plaque. This association was first suggested in 1988, when it was discovered that patients with cardiovascular disease or acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were more likely to have antibodies to C. pneumoniae in their blood.15) Arcari et al.16) studied the link between C. pneumoniae seropositivity and AMI in males aged 30 to 50. The authors found a significantly higher risk of AMI in patients who had high titers to C. pneumoniae immunoglobulin A (IgA) within the previous one to 5-year period. This risk persisted after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors. C. pneumoniae has been detected in more than 40% of atherosclerotic plaques,17) 18) and has been shown (along with cytomegalovirus) to directly disseminate into the arterial vessel walls.19) Smoking, an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, has also been shown to be an independent risk factor for C. pneumoniae seropositivity. It has also been suggested that an exacerbation of C. pneumoniae infection through smoking cigarettes may increase the potential for a systemic infection and therefore increase the chance for development of atherosclerosis.20)

Taken together [the large variety of demonstrated proatherogenic changes set into motion by Chlamydia pneumoniae] suggested that Cpn infections could contribute to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis leading to atherosclerotic plaque growth and increased arterial stenosis. Moreover, Cpn infection may also play a role in the development of an unstable atherosclerotic plaque leading to acute cardio- and/or cerebrovascular events.

Frank R. Stassen 21)

- Cytomegalovirus – Cytomegaloviruses (CMV) can cause acute, persistent and latent infections in both humans and animals. Of all herpes viruses, CMV has been most frequently associated with atherosclerosis in epidemiological, experimental and clinical studies.22) First evidence for a role for CMV in cardiovascular disease comes from studies demonstrating the presence of CMV antigens or nucleic acids in the diseased vascular wall.23) Likewise, CMV nucleic acids have repeatedly been detected in arteries obtained from atherosclerotic patients. More importantly, viral presence was higher in arterial biopsies of patients undergoing reconstructive vascular surgery as compared to patients with early atherosclerosis.24) 25) Also, a positive correlation between CMV and cardiovascular disease has been demonstrated in a variety of studies examining blood markers in diseases.26) Several studies showed the level of CMV antibodies to be gradually related to increased intimal-medial thickening (a measure of the thickness of artery walls). No association were found between low CMV antibody titers and cardiovascular disease, but a clear association was found when the height of the titers was taken into account. Stassen et al. conclude, “In summary, a large variety of data support the hypothesis that CMV contribute to atherogenesis.”27)

- Helicobacter pylori – H. pylori is a known causal agent of several gastrointestinal diseases and has also been implicated in ischemic heart disease (reduced blood supply to the heart muscle). Researchers have proposed a number of mechanisms by which H. pylori may accelerate cardiovascular disease. Ayada states that local inflammatory and immune responses against H. pylori in the stomach can induce systemic (including atherosclerotic lesions) immune reactions due to the chronic nature of the infection.28) There is also speculation that H. pylori may act directly on atherosclerotic plaques, because studies have found its DNA in arterial plaque.29) Other studies suggest that H. pylori may induce platelet aggregation, and thereby play a role in the acute phase of ischemic heart disease.30) A recent meta-analysis indicates that infection with certain more virulent strains of H. pylori may provoke an intense immune response and precipitate coronary events.31)

- Porphyromonas gingivalis – P. gingivalis appears to have an important role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis.32) Gibson et al. showed that immunizing mice against P. gingivalis prevents acceleration of atherosclerosis.33) For more on P. gingivalis and other known periodontal pathogens, see below.

Other evidence

- Common infections predispose a person to stroke and heart attack – In a prospective cohort study, a composite measure of Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 infection, were associated with a higher risk of stroke and other vascular events.34) Diarrhea as an infant (the primary cause of which is microbial infection) has been associated with later cardiovascular disease.35) Further, influenza vaccination was associated with a 50% reduction in the incidence of sudden cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), and ischemic stroke. Both heart attack and stroke have their peak incidence in winter months, which correspond to the time of year when cases of influenza also peak.36)

- Common infections and cardiovascular diseases share the same inflammatory markers – As Costa et al. have pointed out,37) inflammatory markers that are risk factors for heart attack and stroke are also elevated during lower respiratory tract infections as well as during infections such as rheumatic fever, syphilis, diarrhea, malaria, and tuberculosis.38) 39) 40) 41)

- prenatal exposure to influenza and cardiovascular disease – Prenatal exposure to the 1918 influenza pandemic (Influenza A, H1N1 subtype) is associated with >/=20% excess cardiovascular disease at 60 to 82 years of age, relative to cohorts born without exposure to the influenza epidemic, either prenatally or postnatally. These findings suggest novel roles for maternal infections in the fetal programming of cardiovascular risk factors that are independent of maternal malnutrition.42)

- evolutionary analysis suggests cardiovascular disease is not caused by lifestyle or genetic factors – Atherosclerosis has been identified in Egyptian mummies.43) This suggests that whatever factors cause atherosclerosis has existed for at least several millenia. If it were true that a factor such as a harmful allele for a gene or the consumption of fatty foods caused atherosclerosis, the human species would have had several millenia to evolve a defense for this vulnerability to disease or, at the very least, to weed this trait out of the population.44)

Infections May be Causal in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis

A causal relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease?

One of the best known links between two different inflammatory diseases – and a prototypical illustration of successive infection – is the relationship between cardiovascular diseases such as heart attack and stroke, and periodontal disease. A BMJ paper showed a correlation between dental disease and systemic disease (stroke, heart disease, diabetes). After correcting for age, exercise, diet, smoking, weight, blood cholesterol level, alcohol use and health care, people who had periodontal disease had a significantly higher incidence of heart disease, stroke and premature death. More recently, these results were confirmed in studies in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Sweden, and Germany. The magnitude of the association is striking: one study found that people with periodontal disease had a two times higher risk of dying from cardiovascular disease.45)

A 2010 study using pyrosequencing compared the bacterial diversity of atherosclerotic plaque, oral, and gut samples of 15 patients with atherosclerosis, and oral and gut samples of healthy controls.46) The team concluded that there was a high degree of correlation between the presence of certain bacteria in the oral cavity (and to a somewhat lesser extent the gut) with bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. Interestingly, several bacterial taxa in the oral cavity and the gut correlated with plasma cholesterol levels. A 2011 study that compared heart attack victims to healthy volunteers found the heart patients had higher numbers of bacteria in their mouths.47) Their tests on 386 men and women who had suffered heart attacks and 840 people free of heart trouble showed two types – Tannerella forsynthesis and Prevotella intermedia – were more common among the heart attack patients. Interestingly, the total number of species that could be identified in the saliva was the best indicator that somebody was likely to have had a heart attack.

Successive infection dictates that as a person accumulates pathogens in one area of the body, those pathogens likely have mechanisms that allow them to slow the immune response. So, if people harbor greater number of pathogens in their mouths, the immune response may slow in the heart and arteries, making it easier for microbes to spread their as well. The same can be said for the opposite scenario. Also, it may be possible that microbes in the mouth spread toward the heart and arteries, although this has yet to be completely confirmed. However, some of the same bacteria identified in the salivary microbiome, such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis - both of which cause tooth decay48) - have also been identified in atherosclerotic plaque.49) 50)

Work by Kozarov et al. strongly suggests that “the key step [towards systemic infection] is the persistence of intracellular bacteria in phagocytes.” Bacterial strains, they conclude, “once in the circulation, are internalized by phagocytic cells, at which stage selected species avoid immediate killing and spread and colonize distant sites.”51) The group also showed that older patients, when compared to younger controls, have atheromas (plaques) which contain greater proportions of pathogens traditionally associated with periodontitis.52)

Our data demonstrate that the elderly individuals (mean age 67 years) have higher incidence of periodontopathogens in their plaques than the younger individuals…. Species from the Bacteroides family were found in about 17% of the young but in about 80% of the elderly patients, as expected given the association of this family with adult and refractory periodontitis.

Kozarov et al.53)

Given these similarities between the two disease states, along with the evidence presented above, it would be surprising if cardiovascular disease were not also definitively shown to be caused by the communities of microbes.

Tests

C-reactive protein

Main article: C-reactive protein

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an important and evolutionarily ancient component of the innate immune responseThe body's first line of defense against intracellular and other pathogens. According to the Marshall Pathogenesis the innate immune system becomes disabled as patients develop chronic disease..54) CRP has been described as “the prototypical acute-phase reactant to infections and inflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue. in human beings.” In the clinical setting, CRP is used “as a clinical indicator of acute infections and response to treatment, and to assess inflammatory status in chronic diseases.”55) Initially it was thought that CRP might be a pathogenic secretion as it was elevated in people with a variety of illnesses including cancer.56) However, discovery of synthesis in the liver demonstrated that it is manufactured by the human body.

The fact that CRP is an independent predictor of stroke and coronary artery disease but also a key contributor to effective bacterial clearance,57) underscores the importance of microbes in the pathogenesis of these diseases. Some patients on the Marshall ProtocolA curative medical treatment for chronic inflammatory disease. Based on the Marshall Pathogenesis. (MP) have reported temporary increases in CRP, an observation which is consistent with a heightened immune response.

CRP's name comes from its capacity to bind the C-polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae, which provides innate defense against pneumococcal infection.58)

Cholesterol

Main article: Tests: cholesterol and triglycerides (lipids)

The lipid profile is a group of tests that are often ordered together to determine risk of coronary heart disease such as heart attack or atherosclerosis. The lipid profile typically includes:

- high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) — often called “good” cholesterol

- low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) — often called “bad” cholesterol

- total cholesterol

- triglycerides

In many of the diseases the Marshall ProtocolA curative medical treatment for chronic inflammatory disease. Based on the Marshall Pathogenesis. (MP) treats, patients may present with elevated cholesterol. Traditionally, it has been assumed that the elevated cholesterol is causing or contributing to the disease process. However, the alternate hypothesis is no less plausible; in certain inflammatory diseases, the body may be deliberately upregulating levels of cholesterol in order to better manage the disease process. Increasing evidence suggests that this alternative explanation may be true.59) 60) For example, a 2010 study found that several bacterial taxa in the oral cavity and the gut correlated with plasma cholesterol levels61), and another study found that high cholesterol protects against endotoxemia.62)

Both “good” and “bad” forms of cholesterol play pivotal roles in fighting infection, for example, scavenging endotoxins that are released during destruction of pathogenic bacterial forms. While higher levels of total cholesterol are associated with some forms of cardiovascular disease in some patient populations, a number of statistically significant inverse correlations have been found between total cholesterol and various diseases including chronic heart failure, respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, and various acute infections.

Thus, high cholesterol levels among patients on the MP are not seen as a problem but as a sign of the inflammatory response to infection. This means that MP patients do not need to take any measures to lower cholesterol. Over time, as the MP medications work to gradually lower infectious agents causing inflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue., it is expected that cholesterol will return to a normal range. In this same vein, statins, in particular, should not be used to lower cholesterol, because they have effects on the same receptors as olmesartanMedication taken regularly by patients on the Marshall Protocol for its ability to activate the Vitamin D Receptor. Also known by the trade name Benicar. , which may prevent the drug from working effectively.

The cumulative evidence suggests that infections may induce or promote atherosclerosis.63) 64) 65) 66) 67) 68) 69) From our point of view, scientists might readily explain the correlation between infections and atherosclerosis on the basis of the double-edged sword property of the anti-infective immune effects of lipoproteins, and might be able to design more rational and systemic experiments to test this correlation.

R. Han 70)

much confusion has arisen from unclear nomenclature with regard to polyunsaturated fatty acids and the lack of reporting of food sources in prospective cohorts. Data from prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials generally support the replacement of saturated fats with mixed polyunsaturated fatty acids to reduce the risk of death from coronary artery disease. However, it is unclear whether oils rich in omega-6 linoleic acid but low in omega-3 α-linolenic acid also reduce this risk.

Richard P. Bazinet, PhD and Michael W.A. Chu, MD MEd 71)

Key points

Richard P. Bazinet, PhD and Michael W.A. Chu, MD MEd

Homocysteine

Related article: Folic acid and folate

A high level of blood serum homocysteine (known as “homocysteinemia”) is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular disease,72) This has led some to conclude homocysteine “has many deleterious cardiovascular effects.”73) However the amino acid does not appear to cause disease.

Because supplementation of the B vitamins lower levels of homocysteine, one common intervention for altering this risk factor is to supplement patients at risk for cardiovascular disease with folic acid (B9), pyridoxine (B6), and cyanocobalamin (B12). In fact, interventions designed to lower levels of homocysteine with high-dose supplementation of the B vitamins been equivocal, in some cases, seeming to exacerbate disease.

- A 2010 study by House et al. has shown substantial adverse outcomes associated with high-dose B vitamins in patients with advanced diabetic nephropathy.74) These side effects included myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization, and all-cause mortality. According to one commentator, unless other explanations come to light in further analyses of the study, these findings make repetition of a similar trial in this high-risk patient group unethical.

- The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE-2) study, involved 5,522 patients with vascular disease or diabetes mellitus and found no effect of high-dose B6, B9 and B12 cosupplementation on death from cardiovascular disease, whereas the risk of stroke was decreased and the risk of unstable angina requiring hospitalization was increased.75)

Marino et al. showed that eradication of Helicobacter pylori associated with gastritis reduced abnormally high levels of homocysteine.76)

The role of hyperhomocysteinemia in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients remains unclear. 77)

Effect of olmesartan on cardiovascular diseases

Main article: Science behind olmesartan

As is the case with the antivirals,78) antibiotics such as clarithomycin have consistently failed to reduce the rate of cardiovascular disease.79) However, these failures are not conclusive evidence that cardiovascular diseases are not caused by infections nor do they show that these diseases cannot be treated as a chronic infection. These trials did not induce immunopathologyA temporary increase in disease symptoms experienced by Marshall Protocol patients that results from the release of cytokines and endotoxins as disease-causing bacteria are killed. and they did not use high dose olmesartan, which has several benefits beyond its role in activating the innate immune system.

Several prospective, randomized studies show vascular benefits with olmesartan medoxomil: reduced progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with stable angina pectoris (OLIVUS); decreased vascular inflammatory markers in patients with hypertension and micro- (pre-clinical) inflammation (EUTOPIA); improved common carotid intima-media thickness and plaque volume in patients with diagnosed atherosclerosis (MORE); and resistance vessel remodeling in patients with stage 1 hypertension (VIOS).

R. Preston Mason80)

Olmesartan and other ARBs have been used to block various bad effects of Angiotensin II, including heart failure. In this regard, olmesartan has been shown to:-

- protect the heart from damage from inflammation in myocarditis81)

- ameliorate acute experimental autoimmuneA condition or disease thought to arise from an overactive immune response of the body against substances and tissues normally present in the body myocarditis, in rats, suppressing cytotoxic myocardial injury 82)

- prevent acute left ventricular dysfunction83)

- lower C-reactive protein, one of the acute phase proteins that increase during systemic inflammation84)

- act as an antiarrhythmic85)

- block the production of Angiotensin II, thus improving mortality rates in heart failure patients86)

- This study demonstrated that olmesartan reduced angiotensin II and aldosterone levels more effectively than azilsartan, resulting in a stable antihypertensive effect. Olmesartan also had an inhibitory effect on cardiac hypertrophy. Accordingly, it may be effective for patients with increased RAAS activity after cardiac surgery or patients with severe cardiac hypertrophy. 87)

Pharmacotherapy targeting the renin-angiotensin system [the mechanism of the ARBs] is one of the most effective means of reducing hypertension and cardiovascular morbidity.88) 89)

Nien-Chen Li et al.90)

Olmesartan has also been shown to

Jigsaw wrote Since Elizabeth Blackburn won a Nobel prize for telomerase in 2009, I have wondered what effect olmesartan might have on it. Are our telomeres getting shorter and shorter, so we just go POP? while getting healthier and healthier in other respects. This report 96) is re-assuring. Olmesartan raises ACE2 which converts angII to Ang 1-7

Other treatments

- statins – As the 2008 ENHANCE trial illustrates, while high cholesterol is correlated with increased incidence of diseases, lowering cholesterol does not appear to improve human health.97) Indeed, there is some evidence this type of intervention does the opposite.98) The statins have a range of documented negative effects, some of which may be immunopathological. Because statins may interfere with the Marshall Protocol, these drugs are contraindicated.

- diuretics – A diuretic is any drug that elevates the rate of urination and thus provides a means of forced diuresis. There are several categories of diuretics. All diuretics increase the excretion of water from bodies, although each class of diuretic does so in a distinct way. Some diuretics are contraindicated for MP patients.

- diet and exercise – It has been widely hypothesized that a poor diet and a lack of exercise are driving the recent surge in obesity and cardiovascular disease – diseases which are closely linked. But, even the most ambitious intervention programs, which have gone to great lengths to increase rates of exercise and improve eating habits of a population, have failed. One 1999 $200,000 NIH-funded intervention, known as the Pathways program, was performed on two groups of children. Pathways involved a substantial increase in physical education programs, classes about nutrition, significant reduction in fat and calorie content of all school meals, and several other health related measures - and all as part of a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard in studies. The primary goal of the study was to reduce the rate of body fat (a risk factor for cardiovascular disease) in the intervention group, but after the three-year intervention the percent of body fat in both groups was essentially identical. The researchers were unable to explain the failure of their intervention.99) Other such trials for obesity have been equally unsuccessful.100)

- high-dose antibiotics – See above section, Effect of olmesartan on cardiovascular diseases

- beta-blockers – In the aftermath of a heart attack, a beta-blocker will reduce consumption of limited oxygen supplies by slowing a straining heart. This intervention appears to be a sensible one in light of the assumption that heart failure is caused by the heart over-exerting itself. Yet the best study to date has shown that this routinely prescribed class of drugs increases heart failure and overall death.101) 102)

- anti-arrhythmics – Ventricular arrhythmia is correlated with an almost 400% increase in the risk of death from cardiac complications, but a large randomized controlled trial showed that the drugs encainide and flecainide tripled the risk of death from other causes when compared with placebo.103)

- vitamin D – According to results shared at a 2012 conference, patients with 25-DThe vitamin D metabolite widely (and erroneously) considered best indicator of vitamin D "deficiency." Inactivates the Vitamin D Nuclear Receptor. Produced by hydroxylation of vitamin D3 in the liver. levels above 100 nanograms per 100ml, were 2.5 times more likely to have atrial fibrillation as those with more moderate levels (41-80ng/100ml). A 2012 randomized controlled trial conducted over four months showed that daily doses of 2500 IU of vitamin D do not protect against cardiovascular disease risk.104)

The level of vitamin D in our blood should neither be too high nor to low. Scientists have now shown that there is a connection between high levels of vitamin D and cardiovascular deaths. vitamin D is suspected of increasing mortality rate

According to a 2006 estimate, 18% of the global cancer burden is attributable to infectious agents, but almost every indication is that this figure is far too conservative.105) Researchers confined by the logic of Koch's postulatesCentury-old criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a causative microbe and a disease. Koch's belief that only one pathogen causes one disease has now been called into question as multiple postulates are increasingly considered out of date. have looked for a single microbe causing a single disease. Evidence suggests, however, that it is communities of microbes that are responsible for cancer. According to the Marshall PathogenesisA description for how chronic inflammatory diseases originate and develop., chronic microbes persist, in large part, by dysregulating the Vitamin D ReceptorA nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response. (VDRThe Vitamin D Receptor. A nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response.), a key nuclear receptorIntracellular receptor proteins that bind to hydrophobic signal molecules (such as steroid and thyroid hormones) or intracellular metabolites and are thus activated to bind to specific DNA sequences which affects transcription. with a well-characterized role in both the innate immune responseThe body's first line of defense against intracellular and other pathogens. According to the Marshall Pathogenesis the innate immune system becomes disabled as patients develop chronic disease. and metastasis suppression. Indeed one of the hallmarks of cancer is a disruption in the vitamin D endocrine system including high 1,25-DPrimary biologically active vitamin D hormone. Activates the vitamin D nuclear receptor. Produced by hydroxylation of 25-D. Also known as 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcitirol. and slowed activity of the receptor. As they progressively multiply through a process known as successive infectionAn infectious cascade of pathogens in which initial infectious agents slow the immune response and make it easier for subsequent infections to proliferate., microbes elicit an inflammatory response, a response which has been shown to increase over time the risk of metastasis.

Several patients have worked with their doctors to treat their cancer with the Marshall ProtocolA curative medical treatment for chronic inflammatory disease. Based on the Marshall Pathogenesis.. However, the MP appears to be most effective as a preventative measure.

It may be particularly important for MP patients with cancer in the family to avoid caffeine as far as possible.

“It is difficult to assess the practical significance of phagocytic suppression, but our previous work (unpublished) has shown that cancer cells can suppress phagocytosis in a similar manner. If this is the case, caffeine may be aiding in the suppression of immune response in the tumor microenvironment.” 106)

Vitamin D supplementation is ineffective in improving cardiovascular health among various patient populations, including in the presence or absence of vitamin D deficiency. 107)

Patient interviews

neurosarcoidosis, systemic sarcoidosis; spasticity, myasthenia, CNS dysfunction, joint pain, pulmonary, splenic and cardiac involvement

Read the interview

sarcoidosis of the heart, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation

Read the interview

Interviews of patients with other diseases are also available.

Patients experiences

I am happy to report that on the MP, my cardiac symptoms [including angina, cardiac arrhythmias] have been reduced at this point to almost nil.

Even with a good size dose of Verapamil daily and nitroglycerine, pre-MP, I was experiencing cardiac symptoms and events. Once I started the Benicar, they stopped. :) I haven't had to pop sub-lingual nitroglycerine tabs since starting! (Prior to starting the Benicar, I was taking 3 nitro tabs during an event, and then sometimes that wasn't enough.)

Hrts, MarshallProtocol.com

My heart inflammation over the past year has diminished considerably and so I no longer have the pain levels that I once suffered. That to me verifies that I am improving and I am on the right track. I still get heart herxes but they are controllable, and the pressure and arrhythmia, although are very irritating, no longer cause me such concern. I have been through the cycles enough times to have a good feel for what is going on and I can regulate them without too much distress.

CelticLadee, MarshallProtocol.com

When I was diagnosed with MVP [mitral valve prolapse], I was told I might also have dysautonomia, an imbalance of the central nervous system. This is part of something called MVP Syndrome, and the imbalance can cause jittery anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, headaches, physical sensations that mimic low blood sugar, etc. So I decided that I must have this syndrome, because I had all these symptoms. Now I realize it probably all goes back to the sarcoidosis.

If you look at the symptoms list, you'll be amazed at how many of them are Th1 inflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue. disease symptoms. There's also a link to anxiety/depression. When I found this site 10 years ago I was relieved to find that I wasn't the only MVP person suffering with odd things. At different times, I've suffered from about 90% of the MVP Syndrome symptoms listed, but then I found the MP site and it all began to click.

Jen Hicks, MarshallProtocol.com

More information

Hyperuricaemia was associated with an unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile in HF patients. Treatment with low doses of allopurinol did not improve the prognosis of HF patients. 108)

Increased risks per 10 000 person-years found in estrogen plus progestin therapy for 16608 healthy postmenopausal women (studied over 5 years) were 7 more CHD events, 8 more strokes, 8 more PEs, and 8 more invasive breast cancers. 109)

- Links Between Infectious Diseases and Cardiovascular Disease: A Growing Body of Evidence (registration required)

[PMID: 26579677] [DOI: 10.1038/ki.2015.257]

[PMID: 10204048] [DOI: 10.1053/ejvs.1998.0757]

[PMID: 16490835] [DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579979]

[PMID: 27589046] [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.322]

[PMID: 17894024] [DOI: 10.1196/annals.1422.062]

[PMID: 16490832] [DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607358]

[PMID: 18276989]

[PMID: 1872926] [DOI: 10.1016/0021-9150(91)90235-u]

[PMID: 15337206] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.066]

[PMID: 19220338] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02631.x]

[PMID: 12663369] [DOI: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000068645.60805.7C]

[PMID: 16983590] [DOI: 10.1007/s10016-006-9076-1]

[PMID: 2902492] [DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6]

[PMID: 15791511] [DOI: 10.1086/428730]

[PMID: 10193317] [PMCID: 500968] [DOI: 10.1136/jcp.51.11.793]

[PMID: 9866733] [PMCID: 2640250] [DOI: 10.3201/eid0404.980407]

[PMID: 14662717] [DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105513.37677.B3]

[PMID: 10839723] [DOI: 10.1086/315602]

[PMID: 6136795] [DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92529-1]

[PMID: 2541613] [PMCID: 1879908]

[PMID: 2153348] [PMCID: 1877468]

[PMID: 9259669] [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03079-1]

[PMID: 17215796]

[PMID: 18607339]

[PMID: 18599062] [DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.051]

[PMID: 18829178] [DOI: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.04.030]

[PMID: 18220804] [DOI: 10.2174/138161207783018554]

[PMID: 19901154] [PMCID: 2830860] [DOI: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.271]

[PMID: 11281409] [DOI: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00230-6]

[PMID: 12573201] [DOI: 10.1007/s11883-003-0087-x]

[PMID: 17686992] [PMCID: 1948925] [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0611077104]

[PMID: 15375259] [DOI: 10.1126/science.1092556]

[PMID: 5755517]

[PMID: 14614368] [DOI: 10.1097/01.inf.0000095197.72976.4f]

[PMID: 12413502] [DOI: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00102-2]

[PMID: 20198106] [PMCID: 2826837] [DOI: 10.1017/S2040174409990031]

[PMID: 10495769]

[PMID: 10197286] [DOI: 10.1177/204748739900600102]

[PMID: 20937873] [PMCID: 3063583] [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1011383107]

[PMID: 21375559] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00582.x]

[PMID: 10699021] [PMCID: 86374] [DOI: 10.1128/JCM.38.3.1196-1199.2000]

[PMID: 15662025] [DOI: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155018.67835.1a]

[PMID: 17981690] [DOI: 10.2741/2822]

[PMID: 20972353] [DOI: 10.5551/jat.5207]

[PMID: 16513386] [DOI: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.09.004]

[PMID: 15198851] [DOI: 10.1179/096805104225004833]

[PMID: 19000576] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.002]

[PMID: 12813013] [PMCID: 161431] [DOI: 10.1172/JCI18921]

[PMID: 16176663] [DOI: 10.1179/096805105X37402]

[PMID: 14631060] [DOI: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg150]

[PMID: 20377753] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00203.x]

[PMID: 21711511] [PMCID: 3146904] [DOI: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-34]

[PMID: 12196340] [DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030182.35880.3e]

[PMID: 17295657] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00742.x]

[PMID: 17967778] [DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693382]

[PMID: 18551190] [PMCID: 2423423] [DOI: 10.1155/2008/723539]

[PMID: 16781371] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.024]

[PMID: 16277580] [DOI: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2085]

[PMID: 24218530] [PMCID: 3971029] [DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.130253]

[PMID: 12015248] [DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01021-5]

[PMID: 11872979] [DOI: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.00620.x]

[PMID: 20424250] [DOI: 10.1001/jama.2010.490]

[PMID: 16531613] [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa060900]

[PMID: 17005765] [PMCID: 1856853] [DOI: 10.1136/gut.2006.095125]

[PMID: 26762617] [DOI: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0193]

[PMID: 16096289] [PMCID: 1184236] [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.331.7513.361]

[PMID: 21796255] [PMCID: 3141913] [DOI: 10.2147/VHRM.S20737]

[PMID: 16336207] [DOI: 10.1042/CS20050299]

[PMID: 15879491] [DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00078.2005]

[PMID: 15297251] [DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00221.2004]

[PMID: 16939632] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2006.00033.x]

[PMID: 16094406] [DOI: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001933]

[PMID: 16534230] [DOI: 10.1159/000090189]

[PMID: 27086671] [PMCID: 4909997] [DOI: 10.5761/atcs.oa.16-00054]

[PMID: 15531767] [PMCID: 2556374] [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739]

[PMID: 17984484] [DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00189]

[PMID: 20068258] [PMCID: 2806632] [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b5465]

[PMID: 25275251] [DOI: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000313]

[PMID: 19124398] [DOI: 10.1177/1753944707085982]

[PMID: 20202514] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.062]

[PMID: 19892999] [DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.559989]

[PMID: 25001274] [DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03282]

[PMID: 27079876] [PMCID: 4882242] [DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307518]

[PMID: 18376000] [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800742]

[PMID: 14594792] [PMCID: 4863237] [DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.1030]

[PMID: 17028105] [PMCID: 1647320] [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.38979.623773.55]

[PMID: 16271643] [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67661-1]

[PMID: 15863552] [DOI: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157445.67309.19]

[PMID: 22586483] [PMCID: 3346736] [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036617]

[PMID: 20930075] [PMCID: 2952975] [DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00012-10]

[PMID: 27022462] [PMCID: 4777255] [DOI: 10.1002/prp2.180]

[PMID: 28229054] [PMCID: 5290441] [DOI: 10.1159/000452742]

[PMID: 12117397] [DOI: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321]

[PMID: 19922995] [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61913-9]