Main article: Incidence and prevalence of chronic disease

Table of Contents

Obesity

Epidemiology

Obesity rates worldwide have doubled in the last three decades, even as blood pressure and cholesterol levels have dropped, according to several studies published in a 2011 issue of Lancet.1) In 1980, about 5 percent of men and 8 percent of women worldwide were obese. By 2008, the rates were nearly 10 percent for men and 14 percent for women. That means 205 million men and 297 million women were obese. An additional 1.5 billion adults were overweight.

Another team concluded in a recent meta-analysis that if Americans keep gaining weight at the current rate, 75 percent of U.S. adults will be overweight and 41 percent obese by the year 2015. A 2002 paper concluded that “the prevalence of obesity is increasing globally, with nearly half a billion of the world’s population now considered to be overweight or obese.”2)

Obesity is likely to continue to increase, and if nothing is done, it will soon become the leading preventable cause of death in the United States.

Youfa Wang, MD, PhD 3)

Poor diet and exercise as the only cause for obesity?

Related article Whole foods

It has been widely hypothesized that a poor diet and a lack of exercise, are driving what the World Health Organization has termed “an obesity epidemic.”

A 2010 Reuters article stated:

After all, the leading causes of death in the developed world – cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes – all can be prevented to a large degree with exercise, by avoiding tobacco and by eating less fat and sugar and more fruits and vegetables.

But, a 2010 observational study found that increasing fruit and vegetable intake had a marginal impact on risk of cancer.4) According to the research if Europeans increased their consumption of fruit and vegetables by 150g a day (about two servings, or 40% of the WHO's recommended daily allowance), it would result in a decrease of just 2.6% in the rate of cancers in men and 2.3% in women. Even those who eat virtually no fruit and vegetables, the paper suggests, are only 9% more likely to develop cancer than those who stick to the WHO recommendations.

Further, even some of the most ambitious obesity intervention programs, which have gone to great lengths to increase rates of exercise and improve eating habits of a population, have been failures.

One 1999 $200,000 NIH-funded intervention, known as the Pathways program, was performed on two groups of children. Pathways involved a substantial increase in physical education programs, classes about nutrition, significant reduction in fat and calorie content of all school meals, and several other health related measures - and all as part of a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard in studies. The primary goal of the study was to reduce the rate of body fat in the intervention group, but after the three-year intervention the percent of body fat in both groups was essentially identical.5)

Studies such as these suggest that the official dietary advice given over the last decades do nothing to curb the increase in obesity. But just as the lack of effect of using a 10 day course of penicillin for the treatment of an L-form bacteria infection is not evidence of antibiotics not being helpful in the treatment of L-form bacteria, neither is one specific life style intervention evidence of lifestyle measures not having effect.

Other interventions, such as a change in the amount and type of carbohydrate, have shown much greater promise.6) 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) 12)

Attrition was high in most of these studies, as they usually are in any kind of long term diet studies where major diet components are changed. Therefore these studies are just as much a test of the patients’ motivation and the skills of the health professional giving them advice as a pure diet test.

The mechanisms behind the effects of a low carbohydrate, - or a low glycemic, diet on weight loss are generally believed by the authors of the studies foremost to be a result of a reduced insulin secretion. Indeed, insulin administration leads to weight gain13) and insulin suppression leads to weight loss.14)

There could however be other mechanisms at play for the effects of a low-carbohydrate diet, such as changes in the body’s (gut) microbiota. 15)(Note the sharper increase in Bacteriodetes on the low-carbohydrate diet in Figure 1.)

In another study, the relative level of the bacterium Selenomonas noxia in the oral cavity was able to predict obesity with a larger than 98 per cent certainty.16) As infection is the main cause of inflammation in the oral cavity, it is interesting to note that a diet devoid of refined carbohydrates significantly reduces markers of gingival inflammation.17)

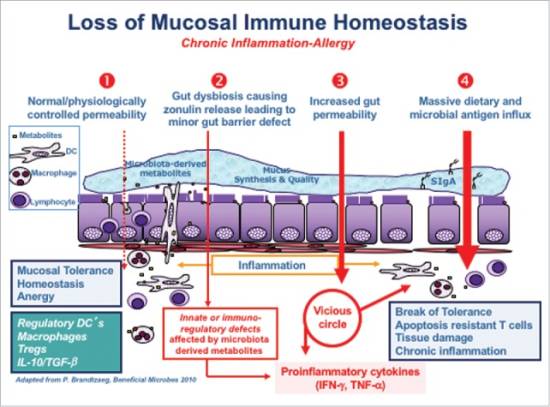

Restoration of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier may include dietary changes, treatment of dysbiosis, digestive supports, and anti-inflammatory therapies.

Evidence of infectious cause

The increase (percentage points) in obesity and overweight in adults was faster than in children (0.77 vs. 0.46–0.49), and in women than in men (0.91 vs. 0.65). If these trends continue, by 2030, 86.3% adults will be overweight or obese; and 51.1%, obese. Black women (96.9%) and Mexican-American men (91.1%) would be the most affected. By 2048, all American adults would become overweight or obese, while black women will reach that state by 2034. In children, the prevalence of overweight (BMI 95th percentile, 30%) will nearly double by 2030. Total health-care costs attributable to obesity/overweight would double every decade to 860.7–956.9 billion US dollars by 2030, accounting for 16–18% of total US health-care costs. We continue to move away from the Healthy People 2010 objectives. Timely, dramatic, and effective development and implementation of corrective programs/policies are needed to avoid the otherwise inevitable health and societal consequences implied by our projections.23)

Shifts in clostridia, bacteroides and immunoglobulin-coating fecal bacteria associate with weight loss in obese adolescents. OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the effects of a multidisciplinary obesity treatment programme on fecal microbiotaThe bacterial community which causes chronic diseases - one which almost certainly includes multiple species and bacterial forms. composition and immunoglobulin-coating bacteria in overweight and obese adolescents and their relationship to weight loss. DESIGN: Longitudinal intervention study based on both a calorie-restricted diet (calorie reduction=10-40%) and increased physical activity (calorie expenditure=15-23 kcal/kg body weight per week) for 10 weeks.Participants:Thirty-nine overweight and obese adolescents (BMI mean 33.1 range 23.7-50.4; age mean 14.8 range, 13.0-16.0).Measurements:BMI, BMI z-scores and plasma biochemical parameters were measured before and after the intervention. Fecal microbiota was analyzed by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Immunoglobulin-coating bacteria were detected using fluorescent-labelled F(ab')2 antihuman IgA, IgG and IgM.

RESULTS: Reductions in Clostridium histolyticum and E. rectale-C. coccoides proportions significantly correlated with weight and BMI z-score reductions in the whole adolescent population. Proportions of C. histolyticum, C. lituseburense and E. rectale-C. coccoides dropped significantly whereas those of the Bacteroides-Prevotella group increased after the intervention in those adolescents who lost more than 4 kg. Total fecal energy was almost significantly reduced in the same group of adolescents but not in the group that lost less than 2.5 kg. IgA-coating bacterial proportions also decreased significantly in participants who lost more than 6 kg after the intervention, paralleled to reductions in C. histolyticum and E. rectale-C. coccoides populations. E. rectale-C. coccoides proportions also correlated with weight loss and BMI z-score reduction in participants whose weight loss exceeded 4 kg.

CONCLUSIONS: Specific gut bacteria and an associated IgA response were related to body weight changes in adolescents under lifestyle intervention. These results suggest interactions between diet, gut microbiota and host metabolism and immunity in obesity.24)

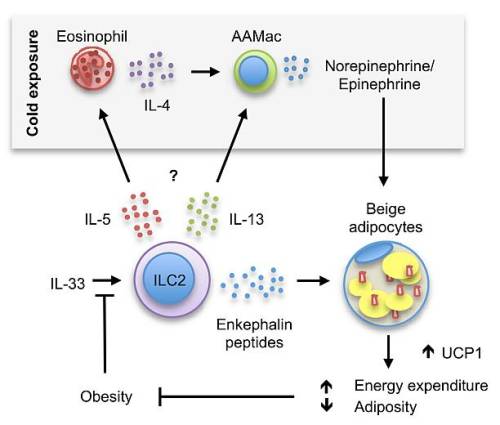

Some studies are indicating that immune cells and molecules are important for regulating metabolism—and are dysregulated in obesity.

Microbe Minded: cholesterol, fat & human metabolism

Obesity and infection

Obesity increases morbidity and mortality through its multiple effects on nearly every human system.

Obesity has a clear but not yet precisely defined effect on the immune response through a variety of immune mediators, which leads to susceptibility to infections.

The available data suggest that obese people are more likely than people of normal weight to develop infections of various types including postoperative infections and other nosocomial infections, as well to develop serious complications of common infections. 25)

Although excess visceral fat is associated with noninfectious inflammation, it is not clear whether visceral fat is simply associated with or actually causes metabolic disease in humans. To evaluate the hypothesis that visceral fat promotes systemic inflammation by secreting inflammatory adipokines into the portal circulation that drains visceral fat, we determined adipokine arteriovenous concentration differences across visceral fat, by obtaining portal vein and radial artery blood samples, in 25 extremely obese subjects (mean +/- SD BMI 54.7 +/- 12.6 kg/m(2)) during gastric bypass surgery at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. Mean plasma interleukin (IL)-6 concentration was approximately 50% greater in the portal vein than in the radial artery in obese subjects (P = 0.007). Portal vein IL-6 concentration correlated directly with systemic C-reactive protein concentrations (r = 0.544, P = 0.005). Mean plasma leptin concentration was approximately 20% lower in the portal vein than in the radial artery in obese subjects (P = 0.0002). Plasma tumor necrosis factor-alphaA cytokine critical for effective immune surveillance and is required for proper proliferation and function of immune cells., resistin, macrophage chemoattractant protein-1, and adiponectin concentrations were similar in the portal vein and radial artery in obese subjects. These data suggest that visceral fat is an important site for IL-6 secretion and provide a potential mechanistic link between visceral fat and systemic inflammation in people with abdominal obesity.26)

Vascular dysfunction

At Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, May 2007 inquiry into TLR4, a key mediator of innate immunityThe body's first line of defense against intracellular and other pathogens. According to the Marshall Pathogenesis the innate immune system becomes disabled as patients develop chronic disease.:

Abstract Vascular dysfunction is a major complication of metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity. The current studies were undertaken to determine whether inflammatory responses are activated in the vasculature of mice with diet-induced obesity, and if so, whether Toll-Like Receptor-4 (TLR4), a key mediator of innate immunity, contributes to these responses. Mice lacking TLR4 (TLR4(-/-)) and wild-type (WT) controls were fed either a low fat (LF) control diet or a diet high in saturated fat (HF) for 8 weeks. In response to HF feeding, both genotypes displayed similar increases of body weight, body fat content, and serum insulin and free fatty acid (FFA) levels compared with mice on a LF diet. In lysates of thoracic aorta from WT mice maintained on a HF diet, markers of vascular inflammation both upstream (IKKbeta activity) and downstream of the transcriptional regulator, NF-kappaBA protein that stimulates the release of inflammatory cytokines in response to infection (ICAM protein and IL-6 mRNA expression), were increased and this effect was associated with cellular insulin resistance and impaired insulin stimulation of eNOS. In contrast, vascular inflammation and impaired insulin responsiveness were not evident in aortic samples taken from TLR4(-/-) mice fed the same HF diet, despite comparable increases of body fat mass. Incubation of either aortic explants from WT mice or cultured human microvascular endothelial cells with the saturated FFA, palmitate (100 micromol/L), similarly activated IKKbeta, inhibited insulin signal transduction and blocked insulin-stimulated NO production. Each of these effects was subsequently shown to be dependent on both TLR4 and NF-kappaB activation. These findings identify the TLR4 signaling pathway as a key mediator of the deleterious effects of palmitate on endothelial NO signaling, and are the first to document a key role for TLR4 in the mechanism whereby diet-induced obesity induces vascular inflammation and insulin resistance.27)

and in March 2007 Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. 28)

Inflammation and diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation. Adipose tissue (AT) may represent an important site of inflammation. 3T3-L1 studies have demonstrated that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activates toll-like receptors (TLRs) to cause inflammation.

For this study, we 1) examined activation of TLRs and adipocytokines by LPS in human abdominal subcutaneous (AbdSc) adipocytes, 2) examined blockade of NF-kappaB in human AbdSc adipocytes, 3) examined the innate immune pathway in AbdSc AT from lean, obese, and T2DM subjects, and 4) examined the association of circulating LPS in T2DM subjects. The findings showed that LPS increased TLR-2 protein expression twofold (P<0.05).

Treatment of AbdSc adipocytes with LPS caused a significant increase in TNF-alphaA cytokine critical for effective immune surveillance and is required for proper proliferation and function of immune cells. and IL-6 secretion (IL-6, Control: 2.7+/-0.5 vs. LPS: 4.8+/-0.3 ng/ml; P<0.001; TNF-alpha, Control: 1.0+/-0.83 vs. LPS: 32.8+/-6.23 pg/ml; P<0.001).

NF-kappaB inhibitor reduced IL-6 in AbdSc adipocytes (Control: 2.7+/-0.5 vs. NF-kappaB inhibitor: 2.1+/-0.4 ng/ml; P<0.001).

AbdSc AT protein expression for TLR-2, MyD88, TRAF6, and NF-kappaB was increased in T2DM patients (P<0.05), and TLR-2, TRAF-6, and NF-kappaB were increased in LPS-treated adipocytes (P<0.05).

Circulating LPS was 76% higher in T2DM subjects compared with matched controls. LPS correlated with insulin in controls (r=0.678, P<0.0001). Rosiglitazone (RSG) significantly reduced both fasting serum insulin levels (reduced by 51%, P=0.0395) and serum LPS (reduced by 35%, P=0.0139) in a subgroup of previously untreated T2DM patients.

In summary, our results suggest that T2DM is associated with increased endotoxemia, with AT able to initiate an innate immune responseThe body's first line of defense against intracellular and other pathogens. According to the Marshall Pathogenesis the innate immune system becomes disabled as patients develop chronic disease.. Thus, increased adiposity may increase proinflammatory cytokines and therefore contribute to the pathogenic risk of T2DM. 29)

Childhood

Childhood obesity may very well be an infectious disease spread by a common cold virus. This is the finding of a recent study that was published in the journal, Pediatrics. According to the study, Adenovirus-36, as it is known in the scientific community, is directly associated with obese children. The association is found in antibodies produced by the previously-infected children. These antibodies – in association with previous animal studies that have looked at the impact of Adenovirus-36 on adult stem cells to produce more fat cells, that also happen to produce more fat – draw the link between the obesity epidemic and this particular virus.

A virus that can increase the production of certain cells offers certain insights on the dangers of viral infections – particularly when considering the spread of cancer and other chronic diseases. Numerous studies have linked viral infections to chronic-fatigue syndrome, prostate cancer, Parkinson's disease, skin cancer, mouth cancer, and even autism and schizophrenia.

The associations between common viruses and the later onset of serious disease presents both a challenge and an opportunity for the scientific community. The challenge is in understanding the basic underpinnings of viruses in general - and the opportunity is in creating vaccinations that can quite effectively remove these chronic diseases from the broader ecology.

Since obesity is seen as an epidemic on its own accord - with the World Health Organization estimating that there are more than 1 billion overweight adults worldwide – the association with a common cold virus should certainly help in the drive toward a vaccination or toward a more permanent solution

Pediatrics, Sept. 2010

see also Ear infections

Fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight.30)

Research

Cellular and molecular players in adipose tissue inflammation in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance. 31)

Adenosine is an endogenous metabolite that is released from all tissues and cells including liver, pancreas, muscle and fat, particularly under stress, intense exercise, or during cell damage. 32)

Here, we report that adenosine level in the cerebrospinal fluid, and hypothalamic expression of A1R, are increased in the diet-induced obesity (DIO) mouse. We find that mice with overexpression of A1R in the neurons of paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus are hyperphagic, have glucose intolerance and high body weight. Central or peripheral administration of caffeine reduces the body weight of DIO mice by the suppression of appetite and increasing of energy expenditure. We also show that caffeine excites oxytocin expressing neurons, and blockade of the action of oxytocin significantly attenuates the effect of caffeine on energy balance. 33)

Higher zonulin levels are associated with higher waist circumference, diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, and increased risk of metabolic diseases 34)

'Western'-style diets, high in fat/sugar, low in fibre, decrease beneficial Firmicutes that metabolise dietary plant-derived polysaccharides to SCFAs and increase mucosa-associated Proteobacteria (including enteric pathogens). 35)

This was of particular interest to us because other research has shown that having more Bacteroidetes may be beneficial because the higher that proportion is, the individual tends to be leaner. With higher Firmicutes, that individual tends to be more obese,“ Holscher said. “We don't know if there is any causality for weight loss, but studies have shown that having a higher fiber diet is protective against obesity. 36) 37)

Weight loss strategy

The best idea may be to plan each meal in two parts.

First, consume the essential part of each meal, containing fresh vegetables and anything else important to your personal needs.

Then take a twenty minute break from eating, after which, consider if at that point you may make a stop until the next meal is due.

Bacteria in the gut produce appetite-suppressing proteins about 20 minutes after a meal

Learn More

[PMID: 12457290] [DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802209]

[PMID: 17510091] [DOI: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007]

[PMID: 20371762] [DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djq072]

[PMID: 14594792] [PMCID: 4863237] [DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.1030]

[PMID: 17341711] [DOI: 10.1001/jama.297.9.969]

[PMID: 15148063] [DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00006]

[PMID: 12640371] [DOI: 10.1067/mpd.2003.4]

[PMID: 16306558] [DOI: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2939]

[PMID: 12912783] [DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.773]

[PMID: 16674818] [PMCID: 1481590] [DOI: 10.1186/1743-7075-3-19]

[PMID: 24829736] [PMCID: 4018597]

[PMID: 17924864] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00686.x]

[PMID: 12587002] [PMCID: 1490021] [DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802227]

[PMID: 17183309] [DOI: 10.1038/4441022a]

[PMID: 19587155] [PMCID: 2744897] [DOI: 10.1177/0022034509338353]

[PMID: 19405829] [DOI: 10.1902/jop.2009.080376]

[PMID: 19901833] [DOI: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333d751]

[PMID: 17652652] [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082]

[PMID: 17183312] [DOI: 10.1038/nature05414]

[PMID: 20804522] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00797.x]

[PMID: 18719634] [DOI: 10.1038/oby.2008.351]

[PMID: 19050675] [DOI: 10.1038/ijo.2008.260]

[PMID: 16790384] [DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70523-0]

[PMID: 17287468] [DOI: 10.2337/db06-1656]

[PMID: 17478729] [DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142851]

[PMID: 17090751] [DOI: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2006]

[PMID: 18326589] [DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.534]

[PMID: 23707515] [PMCID: 3800253] [DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.017]

[PMID: 23460239] [PMCID: 3849123] [DOI: 10.1002/jcp.24352]

[PMID: 28654087] [PMCID: 5490268] [DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15904]

[PMID: 28282855] [PMCID: 5372598] [DOI: 10.3390/ijms18030582]

[PMID: 26011307] [PMCID: 4949558] [DOI: 10.1111/apt.13248]

[PMID: 25527750] [DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092064]

[PMID: 31911661] [PMCID: 7188665] [DOI: 10.1038/s41366-019-0515-9]

[PMID: 19849869] [DOI: 10.1017/S0007114509992182]

[PMID: 20186138] [DOI: 10.1038/oby.2010.22]

[PMID: 17456850] [DOI: 10.2337/db06-1491]

[PMID: 17210919] [PMCID: 1764762] [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104]