Related articles: Detecting bacteria, Koch's postulates

Table of Contents

Sarcoidosis

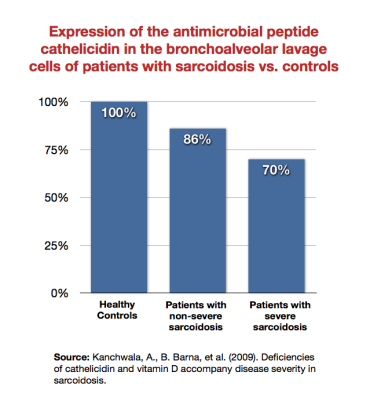

Sarcoidosis or sarc is a multisystem disorder characterized by granuloma, ball-like encapsulations of phagocytic cells driven by microbes. Sarcoidosis is often called the “great masquerader” as there may be several atypical or nonspecific presentations – including not just the lungs but the brain, lymph glands, spleen, liver, skin and heart among others.1)

An infectious etiology of sarcoidosis has long been suspected. Today scientific evidence provides a strong, if not conclusive, link between infectious agents and sarcoidosis.2)

Sarcoidosis was the first disease treated by the Marshall ProtocolA curative medical treatment for chronic inflammatory disease. Based on the Marshall Pathogenesis..3) The FDA's Office of Orphan Products Development has conferred orphan drug status on several MP medications.

Evidence of infectious cause

Today scientific evidence provides a strong, if not conclusive, link between infectious agents and sarcoidosis.4)

Tuberculosis-causing Bacteria Linked to Sarcoidosis, Study Confirms Link 5)

History of conflicting results

An infectious etiology of sarcoidosis has long been suspected and investigated, sometimes with inconsistent results. For example, the histologic similarity of sarcoidosis to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (see discussion of granuloma below) infection led to the “extensive” evaluation of this organism as a possible etiologic factor.6) The findings have been mixed with some investigators finding evidence of M. tuberculosis7) 8) and some failing to confirm this work.9) 10) 11) 12) 13) In their 1996 review of mycobacteria's possible role in sarcoidosis, Zumla and James list 15 studies evaluating a mycobacterial cause of sarcoidosis, only three of which were negative.14)

There appear to several reasons why researchers have failed to definitively link microbes to sarcoidosis in all cases. For one, even today researchers adhere to the antiquated model of disease set forth by Koch's postulatesCentury-old criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a causative microbe and a disease. Koch's belief that only one pathogen causes one disease has now been called into question as multiple postulates are increasingly considered out of date. namely that a pathogen must be: found in all cases of the disease examined, prepared and maintained in a pure culture, capable of producing the original infection, even after several generations in culture, and retrievable from an inoculated animal and cultured again. For all their lingering influence, Koch's postulates never anticipated the era of the human metagenome in which thousands of difficult or impossible-to-culture species of bacteria – rather than just one – contribute to a single disease state. Indeed, the notion of a single causative agent is not in keeping with the worldwide distribution of sarcoidosis.15) Koch's century-old ideas have held science back from understanding how chronic disease occurs because they make no provision for these facts.

Communities of microbes found in patients

The following types and species of bacteria have been found in patients with sarcoidosis, especially the granuloma:

Mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA have been found in the lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis.36)

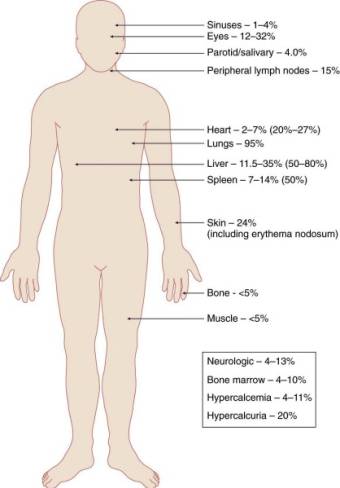

Granuloma

A granuloma is a ball of immune cells associated with various disease states including sarcoidosis, Crohn's, and tuberculosis. (Hence, the term “granulomatous diseases.”) The presence of noncaseating (no tissue death) granuloma of the lungs is the hallmark of sarcoidosis. In sarcoidosis, granuloma are most commonly found in the alveolar septa, the walls of bronchi, and the pulmonary arteries and veins.

At their core, granuloma contain cells from the innate immune system: macrophages and monocytes. Lymphocytes, which are a part of the adaptive or acquired immune system, tend to exist on the periphery or in latter stages of development.37) 38)

Granulomas may represent an extreme form of innate immune dysfunction.39) The macrophages and monocytes in granuloma are infected by intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacteria. When infected, the internal chemistry of innate immune cells is altered such that these cells no longer undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death).40) Significant differences in the expression of apoptosis-related genes were found in peripheral blood of patients with acute onset sarcoidosis.41)

Also, they cease to move towards chemical signals driving an immune response, instead aggregating in clumps. One other side effect of infected macrophages is the dysregulation of the Vitamin D Receptor, leading to the high levels of 1,25-DPrimary biologically active vitamin D hormone. Activates the vitamin D nuclear receptor. Produced by hydroxylation of 25-D. Also known as 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcitirol. characteristic of chronic inflammatory diseases.

In a number of diseases such as tuberculosis, leprosy, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis and syphilis, the formation of a granuloma is widely considered to be an indication of infection.42) Even so, many researchers continue to assume that certain chronic diseases such as sarcoidosis and Crohn's disease are not caused by infection even though they present with granuloma which are similar to those found in diseases known to be infectious.

In fact, the presence of granuloma are entirely consistent with an infectious disease. For example, a Japanese team showed that one could use Propionibacterium acnes in mice to induce lung granuloma mimicking sarcoidosis.43) The distinction between infectious and “non-infectious” granulomatous diseases, may be further complicated by reports such as those by Warrier who reported a case of cutaneous sarcoidosis, the histology of which showed tuberculoid granuloma.44)

Some researchers have argued that, rather than be a host-protective structures formed to contain infection,45) granuloma may be exploited to expand and disseminate an infection. A Cell paper explains how Mycobacteria implicated in tuberculosis may recruit new macrophages to, nascent granulomas.46)

Other evidence

- Difficulty distinguishing sarcoidosis from tuberculosis – Although they have identified a signature that distinguishes healthy individuals from sarcoidosis or tuberculosis patients, the biosignatures of both diseases are nevertheless very similar. Gupta et al. write that differential diagnosis between the two is “very challenging.”47) According to the Max Planck Institute, it is almost impossible to distinguish between tuberculosis and sarcoidosis with just a single signature. A set of different biosignatures is better suited for distinguishing in a first step between diseased and healthy individuals and, in a further step, between the specific diseases.

- Disease appearing in scars – There are several case reports of sarcoidosis lesions forming within scars, which are especially susceptible to infection. That these granuloma often take long periods of time to be realized corresponds with the growth rate of the slow-growing chronic pathogens which the Marshall PathogenesisA description for how chronic inflammatory diseases originate and develop. implicates in chronic disease.48) According to one report, a patient developed sarcoid granuloma fully 50 years after his initial injury.49) Sorabee et al write50) that in addition to reactivation of scars obtained from previous wounds, scar sarcoidosis has been reported at the sites of previous intramuscular injections, blood donation venepuncture sites, scars of herpes zoster,51) sarcoidosis on ritual scarification,52) and at the sites of allergen extracts for desensitisation.53)

- Transmission of disease through blood, bone marrow, organs or other tissues – Organs and tissue from sarcoidosis patients have been known to cause sarcoidosis in the transplanted recipients.54) 55) 56)

- Disease prevalence of small communities in close contact – A number of studies of unrelated people shows that mere proximity seems to be enough to transmit chronic disease. A case-controlled study of residents of the Isle of Man found that 40 percent of people with sarcoidosis had been in contact with a person known to have the disease, compared with 1 to 2 percent of the control subjects.57) Another study reported three cases of sarcoidosis among ten firefighters who apprenticed together.58)

- Familial aggregation of the same disease – A number of studies have shown that spouses have a greater chance of developing the same disease as their partners - a phenomenon that can best be explained if familial aggregationOccurrence of a given trait shared by members of a family (or community) that cannot be readily accounted for by chance. has an infectious cause. One study of sarcoidosis found that among the 215 study participants who had been diagnosed with sarcoidosis, there were five husband-and-wife couples that both had the disease, an incidence 1,000 times greater than could be expected by chance.59) In an analysis of 706 patients and 10,862 first-degree relatives, the 2001 ACCESS study quantified the increased risk relatives of sarcoidosis have in acquiring the illness.60) According to the analysis, first-degree relatives of sarcoidosis patients have a 3.8 times greater risk of having sarcoidosis themselves, with siblings having the greatest risk.

- Kveim reaction – The mKatG protein, a mycobacterial protein, was detected in sarcoidosis tissues and, when injected into sarcoidosis tissues has been shown to induce an adaptive immune response in a subgroup of patients with sarcoidosis.61)

Autoimmune vs. immunosuppressed

Patients with autoimmune disease often show inconsistent signs of autoimmuneA condition or disease thought to arise from an overactive immune response of the body against substances and tissues normally present in the body reactivity.

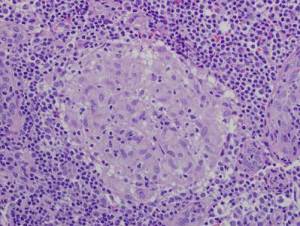

Kanchwala et al. showed that patients with sarcoidosis expressed the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin Family of antimicrobial peptides found primarily in immune cells and transcribed by the Vitamin D Receptor. less than healthy subjects, and that sicker sarcoidosis patients expressed it least of all.62) Wiken et al. showed that there was a reduced TLR2A receptor which is expressed on the surface of certain cells and recognizes native or foreign substances and passes on appropriate signals to the cell and/or the nervous system. mRNA expression in patients with Lofgren's syndrome (a type of acute sarcoidosis).63) Note that TLR2 (which the Marshall Pathogenesis theorizes is downregulated in autoimmune disease states) is expressed by the VDRThe Vitamin D Receptor. A nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response..

Data

from DJ in California. During the summer of 2013 I looked at 2,000 records of people using the Marshall Protocol.

I eliminated all records that had less than 20 messages, as these were usually inquiries into the treatment without actual participation. I eliminated all records from people who had been banned from the site. I eliminated all records from Health Professionals who did not actually have disease. I eliminated all records where I could not find a valid progress report. This left me with 864 meaningful records.

I tried my best to be unbiased as I was expecting to see about a 20% improvement in health of members, or in other words a 20-25% success rate. I was intending to compare this to the 10% success rate I found done on the use of prednisone to treat Sarcoidosis. That double blind report shows that 10% treated with prednisone achieve remission. (BTW remission in Sarcoidosis as far as I can find out is measured rather subjectively)

The following information is what I found:

Sarcoidosis: 236 members; 179 success; 25 no success; 32 unsure

TOTALS: 864 members;573 report success; 119 report no success; and for 172 results are not clear.

SUCCESS RATES: Over all success rate 66.32% Over all unsuccessful 13.77% Over all unsure 19.91%

Sarcoidosis success 75.8%

All Other Th1 diseaseAny of the chronic inflammatory diseases caused by bacterial pathogens. success 59.8%

What we who are a part of this forum, who stuck with the protocol long enough, who endured the IP and were able to keep a doctor, report is that this has a better than 50% success rate.

Tests and diagnosis

No definitive laboratory test diagnostic of sarcoidosis has been identified. For example, sarcoidosis is not diagnosed by the presence of certain antibodies as there usually are none.64)

In the absence of a single agreed upon etiologic agent, sarcoidosis often remains a diagnosis of exclusion, although a typical presentation may strongly suggest the diagnosis. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is established when a compatible clinical and radiographic picture is supported by histologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas in affected tissues and exclusion of other granulomatous diseases (e.g. Crohn's) capable of producing a similar histologic or clinical picture. Note that sarcoidosis is sometimes confused with benign or malignant cancerous tumors.65) Patients should make their doctors aware of any previous sarcoidosis diagnosis (even if only suspected) so sarcoidosis can be investigated as a possible cause of any lumps or tumors.

- pulmonary (lung) function tests – many patients with sarcoidosis have extensive pulmonary fibrosis

- gas transfer coefficient (DLco) – Gas-transfer ability of a patient's lungs

- FEV1 – ???

- angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) – ACE is made by cells in the granulomas. However, ACE levels are not always elevated in those with the disease.

- tuberculin skin test – The tuberculin tine test is the test administered most frequently to screen for tuberculosis, which like sarcoidosis, is a granulomatous disorder.

- x-rays and CT scans – Several imaging technologies are used to show the hallmarks of sarcoidosis in lung tissue. A chest x-ray offers a single scan of the chest while a chest CT relies on x-ray radiation in higher doses than a standard x-ray but allows better pictures of the lung. A CT scan will use a contrast material, typically iodine, to provide superior image quality This may be pose a risk to patients who have renal insufficiency. Usual precautions are to drink plenty of water before and after a CT. These imaging technologies may show granulomas, which appear as a shadow, or enlarged lymph glands in the chest. A staging system is used to classify chest x-rays taken to detect sarcoidosis.

- Stage 0 is a normal chest x-ray.

- Stage 1 is a chest x-ray with enlarged lymph nodes but otherwise clear lungs.

- Stage 2 is a chest x-ray with enlarged lymph nodes plus infiltrates (shadows) in the lungs.

- Stage 3 is a chest x-ray that shows the infiltrates (shadows) are present but the lymph nodes are no longer seen.

- Stage 4 shows scar tissue (fibrosis) in the lung tissue.

The MP medication olmesartanMedication taken regularly by patients on the Marshall Protocol for its ability to activate the Vitamin D Receptor. Also known by the trade name Benicar. blocks formation of fibrotic tissue. However, given that the MP works through generating immunopathologyA temporary increase in disease symptoms experienced by Marshall Protocol patients that results from the release of cytokines and endotoxins as disease-causing bacteria are killed., it would be expected that some sarcoidosis patients on the MP experience a temporary increase in signs of their disease. This would include temporary increases in the appearance of fibrotic tissue and size of lymph nodes a visible on an x-ray. Earlier in the course of therapy, patients are likely to see the most change in the gas transfer coefficient, the DLco, which most doctors don't measure because it can't be done with the simple office spirometer.

Spontaneous remission

Its reputation for spontaneous remissionTheory that diseases go away of their own accord. not withstanding, chronic inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis never go away on their own. It’s not that patients with sarcoidosis don't experience periods where they might feel better. Unfortunately, these intervals are usually a sign that the immune system has become severely compromised. In sarcoidosis, symptom resolution tends to be temporary as evidence by the epidemiological research.

Management and treatment

The Marshall Protocol is a treatment for sarcoidosis. Other treatments (some of which are contraindicated) include the following.

Immunosuppressive medications

For many physicians, immunosuppressive medications are a first-line treatment for sarcoidosis. These drugs suppress the innate immune responseThe body's first line of defense against intracellular and other pathogens. According to the Marshall Pathogenesis the innate immune system becomes disabled as patients develop chronic disease., which provides some patients with temporary symptom palliation, because they reduce immunopathology, the bacterial die-off reaction.

- corticosteroidsA first-line treatment for a number of diseases. Corticosteroids work by slowing the innate immune response. This provides some patients with temporary symptom palliation but exacerbates the disease over the long-term by allowing chronic pathogens to proliferate. – There are no studies which show that glucocoritcoids (corticosteroids) improve long-term prognosis in the treatment of illness. Van den Bosch and Grutters write66), “Remarkably, despite over 50 years of use, there is no proof of long-term (survival) benefit from corticosteroidA first-line treatment for a number of diseases. Corticosteroids work by slowing the innate immune response. This provides some patients with temporary symptom palliation but exacerbates the disease over the long-term by allowing chronic pathogens to proliferate. treatment.” The 2003 NIH ACCESS study67), the largest and most ambitious to date, validates that these drugs are ineffective for sarcoidosis patients, even for a time period as short as two years. For even short periods of time, steroid use can become genuinely addictive. Research shows that any kind of short-term symptomatic improvement from corticosteroid use does not last, and that over the longer term, use of the drugs entales a litany of side effects. For their own safety, patients on the Marshall Protocol (MP) must wean off of them as opposed to discontinuing them outright.

- TNF-alpha inhibitors – Tumor necrosis factor-alphaA cytokine critical for effective immune surveillance and is required for proper proliferation and function of immune cells. or TNF-alphaA cytokine critical for effective immune surveillance and is required for proper proliferation and function of immune cells. is a cytokineAny of various protein molecules secreted by cells of the immune system that serve to regulate the immune system. critical for effective immune surveillance.68) TNF-alpha inhibitors, also known as TNF blockers, anti-TNF drugsDrugs which interfere with the body's production of TNF-alpha - a cytokine necessary for recovery from infection or TNF-alpha antagonists, are drugs which interfere with the body's production of TNF-alpha.69) Anti-TNF drugs are expensive, ineffective at treating chronic disease and have a number of adverse effects such as increase risk of serious infection such as mycobacterial infection.70) 71)

- inhalers, steroid – Steroid inhalers suppress the innate immune response and delay progress on the MP. MP patients taking steroid inhalers should work with their physicians to switch drugs such as a bronchiodilator inhaler.

Lung transplantation

In the face of end-stage pulmonary sarcoidosis, many pulmonologists advise patients to consider lung transplantation. While a number of patients with advanced forms of sarcoidosis (including many who need supplemental oxygen) have done well on the MP, lung transplantation for sarcoidosis is problematic for several reasons.

A lung transplant fails to address the underlying cause, and, as a result, disease reoccurrence is not uncommon. A Danish study showed that lungs implanted in sarcoid patients are reinfected with granulomas five months later (reinfection was determined to come from the recipient patient)72) while another study showed recurrent sarcoidosis occurred as late as 56 months after the procedure.73)

According to several observational studies, the median survival time of sarcoidosis patients after they receive a transplant has been reported to be about 4.7 years74) – about half that of other major transplanted organ recipients.

Finally, any quality of life during time following transplant is limit. To ward off tissue rejection and survive several years, patients must take a cocktail of anti-rejection and immunosuppressive drugs, classes of drugs which entale a number of side effects.

There are at least several patients who have chosen to do MP rather than be on a Transplant List.

Other treatments

- inhalers, bronchiodilator – A bronchodilator is a substance that dilates the bronchi and bronchioles, decreasing airway resistance and thereby facilitating airflow. A bronchodilator is delivered either by Medicated Dose Inhalers (MDI) or Dry Powder Inhalers (DPI) may be useful to reduce shortness of breath (dyspnea). As opposed to steroid inhalers, which are immunosuppressive, it is okay and sometimes essential to use bronchodilators while on the MP. Note that some combination products including Seretide, Advair, and Symbicort contain both bronchiodilating and steroidal medications and are therefore contraindicated.

- supplemental oxygen – Some patients with obstructive lung diseases have trouble getting enough oxygen by breathing normally. For these patients, a prescription for supplemental oxygen should be seriously considered. Supplemental oxygen may be useful or necessary in some cases even though it may be needed only for a few hours a day for a few months. Some patients may need oxygen when flying or at high altitude.

- methotrexate – Methotrexate (MTX) and sulfasalazine are antimetabolite antibiotics with actions similar to Bactrim DS, an MP antibiotic. MP patients taking MTX or sulfasalazine must discontinue those medications.

Vitamin D metabolism

Main article: Metabolism of vitamin D and the Vitamin D Receptor

Under most normal conditions, serum levels of the active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin DPrimary biologically active vitamin D hormone. Activates the vitamin D nuclear receptor. Produced by hydroxylation of 25-D. Also known as 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcitirol. (1,25-D), are constant throughout the year (no variability due to sun exposure),75) but there is no such tight biochemical regulation in at least some chronic inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis. Patients with sarcoidosis tend to have high levels of 1,25-D. As the article Metabolism of vitamin D and the Vitamin D Receptor explains, these high levels may be a direct outcome of microbes' effect on slowing activity of the VDR. It is also an indication of innate immune dysfunction.

It is sometimes thought that the liver and kidney are the only sites for conversion of 25-DThe vitamin D metabolite widely (and erroneously) considered best indicator of vitamin D "deficiency." Inactivates the Vitamin D Nuclear Receptor. Produced by hydroxylation of vitamin D3 in the liver. into 1,25-D, but this process happens outside those organs – not coincidentally, at the very sites where patients report symptoms of chronic disease. High levels of 1,25-D and the enzyme which leads to the production of 1,25-D, 1 α-hydroxylase, have been found at various locations where the human body needs a strong host defense.76) Zehnder et al found increased expression of the enzyme 1 α-hydroxylase – the enzyme which converts 25-D into 1,25-D – in the skin cells of sarcoidosis patients where sarcoidosis patients tend to have disease symptoms.77) They write:

In particular, the expression of 1α-OHase [1 α-hydroxylase] by activated macrophages and epidermal keratinocytes [skin cells] suggests a role for 1,25(OH)2D3 [1,25-D] as an immunomodulatory and/or antiproliferative hormone.

A number of studies have demonstrated that the level of the hormone 1,25-D rises in patients with certain chronic diseases. Kavathia et al. found that in patients with sarcoidosis, those with high serum levels of 1,25-D have more pronounced chronic treatment needs.78)

Calcium metabolism

Hypercalcemia (excess levels of calcium in the blood) and hypercalciuria (excessive urinary calcium excretion) are frequently associated with the granulomatous diseases. Prevalence data suggests that 30 to 50 percent of patients with sarcoidosis have hypercalciuria and 10 to 20 percent have hypercalcemia.79) 80) Until recently, some researchers suggested that these processes were caused by high levels of 1,25-D.81) 82) As a result, patients with granulomatous disease are widely cautioned to limit sunlight exposure and vitamin D ingestion – recommendations that are generally not offered to patients with other chronic inflammatory diseases. Even pro-vitamin D advocates such as Michael Holick, M.D. have issued such cautions for high-dose supplementation of vitamin D in granulomatous diseases.83)

However, according to the Marshall Pathogenesis, any essential discrepancy in calcium/VDR metabolism between the granulomatous and non-granulomatous diseases is limited. The prevalence data suggests as much. Not everyone who has sarcoidosis gets hypercalcemia, and a large number of patients with other diseases such as breast and lung cancers are at risk for the condition.84) Further, in many diseases for which hypercalcemia is not suspected, the condition tends to go underdiagnosed.

Consistent with its classically understood role in maintaining bone health, the Vitamin D ReceptorA nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response. does appear to play at least some direct role in calcium regulation: a 2010 paper showed that the VDR signals stem cells responsible for osteoblast (bone-building) activity.85) But, researchers have since emphasized the role of estrogens and the estrogen receptor in maintaining bone health.86) In a 2007 study in Cell, Nakamura and colleagues showed that, in a female mouse model, removing estrogen receptor alpha in osteoblasts demonstrated that estrogen directly induces osteoclast apoptosis.87) The loss of estrogen among women at menopause may play some role in this process, but it is too soon to say this relationship is causal. Nakamura's work was done in otherwise healthy mouse cells rather than in human cells – which may be infected by pathogens. If such cells were infected, supplementation with estrogen would not address the underlying disease process.

Incidence and prevalence

An analysis of the 2001 ACCESS study challenged the widely held stereotype that the American patients most often affected by sarcoidosis are African-Americans and under 40.88)

Commonly involved organs

Sarcoidosis can affect any organ, initially presenting with one or more of the following abnormalities (in order of frequency according to the 2001 ACCESS study, which used data collected by pulmonologists).89)

Lung (pulmonary)

- alveolitis – InflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue. in sarcoidosis does cause fluid in the lungs. Alveolitis is inflammation of the tiny sac-like air spaces where the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen take place. When the alveoli are filled with fluid, there is less exchange of gases.

- atalectasis – The lack of gas exchange within alveoli, due to alveolar collapse or fluid consolidation. It may affect part or all of one lung. It is a condition where the alveoli are deflated, as distinct from pulmonary consolidation.

- bronchiectasis – A disease state defined by localized, irreversible dilation of part of the bronchial tree. It is classified as an obstructive lung disease, along with emphysema, bronchitis and cystic fibrosis.

- crackles – Crackles, crepitations, or rales are the clicking, rattling, or crackling noises that may be made by one or both lungs of a human with a respiratory disease during inhalation.

- diffuse interstitial lung disease – A group of lung disorders in which the deep lung tissues become swollen and scarred. Caused by swelling and scarring of the air sacs (alveoli) and their supporting structures (the interstitium). This leads to reduced levels of oxygen in the blood.

- Eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by a large number of eosinophils in the lungs, usually in the absence of an infectious disease. Eosinophils are one of the white blood cells and are classified as a granulocyte. 90)

- hyperinflation – Hyperinflation is sometimes called “air trapping” and may be helped by measures such as pursed lip breathing. Pursed lip breathing can help release air trapped in the lungs and can help relieve the feeling of shortness of breath, if it's due to hyperinflation. In some cases, supplemental oxygen might be useful in overcoming hyperinflation. This Medscape article (registration required) discusses how supplemental oxygen facilitates lung emptying.

- obstructive lung disease – It's a little-recognized fact that sarcoidosis can cause PFTs results to indicate obstructive lung disease (sarcoidosis is considered a restrictive lung disease). This is because chest lymph nodes may become so enlarged they compress airways and/or granulomas themselves may obstruct airways. This article explains the difference between restrictive and obstructive lung disease.

- pulmonary fibrosis – Formation or development of fibrous connective tissue in the lungs. Also called scarring, the creation of collagen allows the body to encase pathogens which have been missed by the immune system. Symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis include shortness of breath, a chronic dry cough, and chest discomfort. The angiotensin blockade (put into place by olmesartan) inhibits the formation of new fibrotic tissue. ALSO This study suggests that mast cells may contribute to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. 91)

Managing respiratory symptoms

Main article: Managing respiratory symptoms

A variety of strategies that do not involve medication are available for patients who have uncomfortable respiratory symptoms including breathing exercises, getting more fluids, rest, and others. Also, patients have reported relief taking guaifenesin, using bronchodilator inhalers (steroid inhalers are contraindicated), and nebulizers. Supplemental oxygen may be useful or necessary in some cases even though it may be needed only for a few hours a day for a few months.

While it is certainly possible to contract an acute respiratory infection while on the Marshall Protocol, many symptoms of immunopathology mimic those of an acute respiratory infection. Early recognition and effective management of immunopathology are very important when a patient has respiratory symptoms. Any symptom that correlates with MP therapy may be due to immunopathology.

Emergency medical personnel should know that a patient is on the MP. The article Notice for health care providers provides information that emergency medical personnel need to know.

A cough can develop at any time in sarcoidosis. It can be related to anything from upper respiratory involvement and post-nasal drip to chest involvement or even triggered by exposure to dust, fungus, odors or fumes.

Belinda, MarshallProtocol.com

Skin (cutaneous sarcoidosis)

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis are common and varied, and one patient can have different types of sarcoid skin lesions at the same time. Because of its diverse skin manifestations, sarcoidosis is most frequently diagnosed by a dermatologist. When a patient with sarcoidosis presents with skin problems, physicians should be alert to sarcoidosis as likely the source of these problems.

Lupus pernio

Lupus pernio is not another disease, nor is it related to lupus. Lupus pernio is a chronic plaquelike hardening of the face, usually appearing with violet discoloration of the cheeks, lips, nose, and ears. It can erode into cartilage or bone. Lupus pernio lesions can be permanently disfiguring and cause a patient to feel embarrassed, particularly since they may be noticeable on facial areas so visible to the public.

Sometimes lupus pernio lesions will have an appearance of small “beads” along their edge, especially if the sore is on the rim of the nose. Like some other cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions, lupus pernio can appear at sites of old scars or trauma97) as well as in the upper respiratory tract98) – both sites of which can be quite resistant to the standard immunosuppressive therapies. These lesions can occur when the nose, face or hands are exposed to cold or wind, so it's a good idea for patients with sacroidosis to keep these areas protected from wind and cold. Avoiding exposure to bright lights is also an important preventative measure. Lupus pernio is said to be the skin lesion most characteristic (a diagnostic indicator) of sarcoidosis99), but not all sarcoidosis patients have these skin lesions.

Erythema nodosum (subcutaneous nodules)

Erythema nodosum are raised red, tender nodular lesions, generally but not exclusively on the anterior surface of the lower part of the leg. These lesions do not represent granulomatous involvement of the skin. Rather, the histopathology is primarily that of a panniculitis (inflammation of the fatty layer under the skin), with cellular inflammation and edema of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The presence of erythema nodosum is commonly observed in other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.100)

Eye (ocular sarcoidosis)

The reported frequency of ocular manifestations for sarcoidosis varies according to the source and group studied, but may be as high as 70%.101) In the eye, the common sites of involvement are the skin of eyelid, conjunctiva, uveal tract, retina, optic nerve and lacrimal gland.102) Common symptoms of ocular sarcoidosis include:

- uveitis – Swelling and irritation of the uvea, the middle layer of the eye. Most common is anterior uveitis, however, over a quarter of patients will have inflammation at the posterior of the eye, including retinitis pars planitis. according to the Cleveland Clinic, “Complications of uveitis may include glaucoma, cataract, abnormal blood vessel growth, fluid within the retina and vision loss.”

- Sjogren's (Sicca) – Sjogren's and sarcoidosis are both described in the standard literature as a collection of symptoms. Sjogren's is known to be related to diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, lupus, scleroderma and polymyositis. Many sarcoidosis patients manifest the same symptoms as described in Sjogren's syndrome (dry eyes and mouth, decreased tears and saliva, and resulting dental caries). Sjogren's is reportedly seen in about half of patients.

- blurred vision

- increased tearing

- dry eyes – may require natural tears or other lubricants

- cataracts

- conjunctiva103)

Some asymptomatic patients still have active inflammation. Initially asymptomatic patients with ocular sarcoidosis can eventually develop blindness. Therefore, it is recommended that all patients with sarcoidosis receive a dedicated ophthalmologic examination.

Columbia University researcher Emil Wirotsko identified cell wall deficient bacteria – which he described as “mollicute-like organisms” – in the vitreous fluid of sarcoidal eyes.104) He further showed that the introduction of these microbes into mouse model effectively reproduced the chronic inflammatory process and granuloma that are the hallmark of sarcoidosis.

Lymph nodes

A lymph node, also called a gland, is a small ball-shaped organ of the immune system, distributed widely throughout the body and linked by lymphatic vessels. Lymph nodes are garrisons of B, T, and other immune cells. Lymph nodes are found all through the body, and act as filters or traps for foreign particles.

Lymph nodes play a vital role in the body's ability to fight off microbes. During an infection, the lymph nodes can expand due to intense B-cell proliferation in the germinal centers, a condition commonly referred to as “swollen glands.” Lymphadenopathy refers to “disease of the lymph nodes.” It is, however, almost synonymously used with “swollen or enlarged lymph nodes.” Lymphadenopathy can occur anywhere there are lymph node, but especially the neck, armpits, groin, or chest. Enlarged or tender glands can often be detected by low-tech means: visually or by palpation. Lymph nodes deep in the groin or beneath the ribs in the chest can be monitored with imaging such as chest x-ray, CT or PET scan.

Like any sarcoidosis symptom, lymphadenopathy may flare with immunopathology, resulting in enlarged and/or tender lymph nodes. The increase in the size of lymph nodes is consistent with an immunostimulatory therapy such as the Marshall Protocol. However, in later stages of sarcoidosis the lymph nodes shrink as their functionality decreases. This may be because they become too damaged to function. It is not unusual for lymph nodes to be calcified in sarcoidosis patients.105)

While it is true that chest pain can be due to cardiac involvement, it may simply be due to other problems brought on by sarcoidosis such as enlarged lymph nodes which can cause pressure, crowding and pain in the chest. Enlarged lymph noses can also result in bronchial obstructions.

Management

Related article: Massage and other manipulation therapies

Massage can increase lymphatic flow106) as can osteopathic manipulation.107) Patients seeking this kind of therapy should look for therapists competent in techniques to help the lymphatic system and familiar with the needs of patients with chronic illness.

Liver

Sarcoidosis of the liver is not uncommon.108) According to Richard W Goodgame, MD, “The prevalence of hepatic granulomas in sarcoidosis is 65%. In a study of 100 patients with hepatic sarcoidosis, the majority of patients were asymptomatic and had normal abdominal examinations.”

The angtiotensin receptor blocker olmesartan has been shown to reduce liver fibrosis109) and aid liver healing.110) Some patients with sarcoidosis of the liver are mistakenly told they have “fatty liver disease” or cirrhosis.

Spleen

The reported frequency of splenomegaly, enlargement or inflammation of the spleen, in sarcoidosis has ranged from 1% to 40%.111)

Neurologic (neurosarcoidosis)

Neurosarcoidosis (sometimes shortened to neurosarcoid) refers to sarcoidosis involving the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). It can have many manifestations, but abnormalities of the cranial nerves (a group of twelve nerves supplying the head and neck area) are the most common. It may develop acutely, subacutely, and chronically. Approximately 5-10% of people with sarcoidosis of other organs develop central nervous system involvement. Only 1% of people with sarcoidosis will have neurosarcoidosis alone without involvement of any other organs. Diagnosis can be difficult, with no test apart from biopsy being completely reliable.

Psychiatric problems occur in 20% of cases; many different disorders have been reported, e.g. depression and psychosis. Peripheral neuropathy has been reported in up to 15% of cases of neurosarcoidosis.112)

Managing neurological symptoms

Main article: Managing neurological symptoms

Cardiac

According to a 2003 study of Dutch patients, 30% of people with sarcoidosis suffer from chest pain.113) A similar proportion of sarcoidosis patients were found to have cardiac involvement upon autopsy.114) A third paper found that perhaps 50% of sarcoidosis patients have cardiac involvement that is not diagnosed115).

While it is true that chest pain can be due to cardiac involvement,116) it may simply be due to other problems brought on by sarcoidosis such as enlarged lymph nodes which can cause pressure, crowding and pain in the chest.

All sarcoidosis patients are cautioned to assume they may have unrecognized cardiac involvement and to control their level of immunopathology accordingly.

Managing cardiac symptoms

Main article: Managing cardiac symptoms

While a severe cardiac immunopathological reactionA temporary increase in disease symptoms experiences by Marshall Protocol patients that results from the release of cytokines and endotoxins as disease-causing bacteria are killed. is rare, it has the potential to be life-threatening. Therefore, health care providers are cautioned to be on the alert for cardiac symptoms in all their patients. Also, patients with risk factors or legitimate cause for concern should know when seek medical attention.

Other

- Heerfordt's syndrome – also referred to as uveoparotid fever, Heerfordt-Mylius syndrome, Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome, and Waldenström’s uveoparotitis, is a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis. The symptoms include inflammation of the eye (uveitis), swelling of the parotid gland, chronic fever, and in some cases, palsy of the facial nerves.

- mouth – Symptoms of sarcoidosis involvement in the mouth include: sores on or swelling of the face, tongue, mouth, gums or inside the cheeks,117) 118) 119) 120) gingivitis,121) too much or more commonly too little saliva, 122) and gum disease and increased dental cavities. Biopsy of the mouth often leads to diagnosis.

- sleep apnea – Sleep apnea is the temporary absence of breathing during sleep. Sarcoidosis patients have a higher incidence of sleep apnea than the general population.126) Sarcoidosis itself can cause obstuctive sleep apnea due to the fact that sarcoid inflammation and granulomas can obstruct upper airway passages. In addition, use of the common therapy for relieving sarcoidosis symptoms: Prednisone, which is a corticosteroid, usually results in significant weight gain – which itself contributes to sleep apnea.

Patient interviews

sarcoidosis of the heart, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation

Read the interview

neurosarcoidosis, systemic sarcoidosis; spasticity, myasthenia, CNS dysfunction, joint pain, pulmonary, splenic and cardiac involvement

Read the interview

Interviews of patients with other diseases are also available.

Patients experiences

I just returned from a wonderful family vacation in Disney World. I was so excited that I was able to walk and keep up with my family… mostly, anyway and didn't need a wheelchair! When we booked our trip 10 months ago, I was planning to reserve a wheelchair to access the monorail and keep up with my family. As the summer progressed and I was feeling better I was confident that I was able to walk up ramps, etc. and did! The other wonderful news I have is that I was able to fly round trip from Alaska to Florida keeping my oxygen saturation above 90% without supplemental oxygen! I had my approved POC with Doctor's prescription etc. if needed, but my saturation was good as was my heart rate between 55 bpm and 75 bpm! I am thrilled!

Sue Lyons, MarshallProtocol.com

It's been a long time since I posted and am ashamed of being so remiss. I do not go on the computer very often but I do read everyone's post especially if it has information that I want to know.

I have been on the MP for almost five years now and have seen a lot of improvement although I still have a good way to go. I am down to taking only benicar 40mg every six hours and feel that it is helping me a lot. Before MP I was on a lot of medications but most of the symptoms have been resolved.

My cholesterol has dropped to a reasonable level, blood pressure has dropped, bone density has improved. Before MP I was on so many medications for high blood pressure, osteoporosis, high cholesterol. I still have occasional dizziness and my hearing has become very poor, I cannot walk without a walker. I had another MRI in November last year and my doctor said that the tumor in my brain is still very small but it is benign and it is really of no significance so I was pleased about that.

I went in March and had a screening test and all the tests came back normal which is very encouraging.

I will try and post regularly as I have a little more time on my hands now.

Hester, MarshallProtocol.com

I am doing well. I completed phase three and right now I am on Benicar every six hours and max dose of zith every eight days as per Dr. Bleny's instruction. As I posted earlier, in January this year I had a chest x-ray which showed improvement. My sun tolerance has improved and my energy as well. My major problem at the moment is my knee. I think this will also go away with time.

Some of my blood markers are off:

I am currently taking Soda Bicarb tablets every day.

Asif, MarshallProtocol.com

Read more

[PMID: 15103279]

[PMID: 17560303] [DOI: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.003]

[PMID: 15246025] [DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2003.10.001]

[PMID: 28159576] [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.021]

[PMID: 7617973]

[PMID: 1373786] [DOI: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90536-c]

[PMID: 1349051] [DOI: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90535-b]

[PMID: 1586060] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1142]

[PMID: 8542146] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.1.8542146]

[PMID: 9310026] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9612035]

[PMID: 10193375] [PMCID: 1745089] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.53.10.871]

[PMID: 10408488] [DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12310-3]

[PMID: 8711683] [PMCID: 473601] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.51.5.530]

[PMID: 6184266]

[PMID: 1067009] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47035.x]

[PMID: 8865408]

[PMID: 1582344]

[PMID: 8391908]

[PMID: 9596840]

[PMID: 9561361] [DOI: 10.1007/s004170050078]

[PMID: 11773116] [PMCID: 120089] [DOI: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.198-204.2002]

[PMID: 10472755] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01844.x]

[PMID: 12453366] [PMCID: 2738555] [DOI: 10.3201/eid0811.020318]

[PMID: 8862592] [PMCID: 229225] [DOI: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2240-2245.1996]

[PMID: 17088357] [PMCID: 1828402] [DOI: 10.1128/IAI.00732-06]

[PMID: 16926652] [DOI: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000239554.01068.94]

[PMID: 16113515] [DOI: 10.1159/000087688]

[PMID: 10834540] [DOI: 10.1007/s004280050460]

[PMID: 10418818]

[PMID: 18156583] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.2006.077008]

[PMID: 15948792] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00449.x]

[PMID: 11930323] [DOI: 10.1086/339962]

[PMID: 3486154] [DOI: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80040-5]

[PMID: 12540568] [PMCID: 145351] [DOI: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.864-871.2003]

[PMID: 16086183] [DOI: 10.1007/s00430-005-0239-4]

[PMID: 11641969]

[PMID: 14527294] [DOI: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091033]

[PMID: 20424662] [DOI: 10.18926/AMO/32852]

[PMID: 17656979]

[PMID: 19135887] [PMCID: 3134310] [DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.014]

[PMID: 22759770] [DOI: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283560809]

[PMID: 17243430]

[PMID: 19094856]

[PMID: 15640432] [PMCID: 1743183] [DOI: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.018796]

[PMID: 10086879] [DOI: 10.1080/000155599750011903]

[PMID: 2917808] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb01305.x]

[PMID: 1458650] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00236.x]

[PMID: 12002380]

[PMID: 7951107]

[PMID: 11607780] [DOI: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703192]

[PMID: 16844727] [PMCID: 2121155] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.2006.062836]

[PMID: 8214953] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.974]

[PMID: 17684288] [DOI: 10.1513/pats.200607-138MS]

[PMID: 11739139] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2106001]

[PMID: 17684291] [PMCID: 2647598] [DOI: 10.1513/pats.200608-155MS]

[PMID: 20813038] [PMCID: 2939603] [DOI: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-121]

[PMID: 8620732] [DOI: 10.1378/chest.109.2.535]

[PMID: 16168469] [DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.002]

[PMID: 16946094] [DOI: 10.1183/09031936.06.00105805]

[PMID: 14620163]

[PMID: 16331857] [DOI: 10.1007/3-540-37673-9_10]

[PMID: 16705109] [DOI: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275]

[PMID: 12614731] [DOI: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00545-0]

[PMID: 16135738] [DOI: 10.1183/09031936.05.00127404]

[PMID: 9741371] [PMCID: 1745184] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.53.4.281]

[PMID: 19134524] [DOI: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.10.014]

[PMID: 19444938] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.001]

[PMID: 18981129] [PMCID: 2596683] [DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7090]

[PMID: 11158062] [DOI: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7220]

[PMID: 20071158] [PMCID: 4778713] [DOI: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.004]

[PMID: 2673772]

[PMID: 10782361] [DOI: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395]

[PMID: 10363752] [DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00474.x]

[PMID: 17634462] [DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra070553]

[PMID: 1460860]

[PMID: 20813899] [DOI: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279216]

[PMID: 19751412] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04954.x]

[PMID: 17803905] [DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.025]

[PMID: 11734441] [DOI: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046]

[PMID: 28705588] [DOI: 10.1016/j.alit.2017.06.010]

[PMID: 16227329] [PMCID: 2080703] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.2005.042838]

[PMID: 16198969] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.02.006]

[PMID: 15863633] [DOI: 10.1183/09031936.05.00083404]

[PMID: 15449010] [DOI: 10.1007/s00330-004-2480-4]

[PMID: 8252776] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb02256.x]

[PMID: 1013937] [PMCID: 470492] [DOI: 10.1136/thx.31.6.660]

[PMID: 17041433] [DOI: 10.1097/01.RHU.0000062509.01658.d1]

[PMID: 15307561] [DOI: 10.1080/00365540410027184]

[PMID: 18021432] [PMCID: 2169207] [DOI: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-46]

[PMID: 11217257]

[PMID: 15512984] [DOI: 10.1080/09273940490895353]

[PMID: 2801045] [DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb01626.x]

[PMID: 8617038] [DOI: 10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80343-6]

[PMID: 2250109] [DOI: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12514347]

[PMID: 16314677]

[PMID: 8036338]

[PMID: 19303015] [DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.081]

[PMID: 12871826] [PMCID: 1573934] [DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705339]

[PMID: 8532960]

[PMID: 17636138] [DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.124263]

[PMID: 12737278]

[PMID: 12360650] [DOI: 10.3810/pgm.2002.09.1316]

[PMID: 9608713]

[PMID: 15316439] [DOI: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000136403.32451.aa]

[PMID: 16456999] [DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0021]

[PMID: 16610265] [DOI: 10.12968/denu.2006.33.2.112]

[PMID: 9127377] [DOI: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90145-1]

[PMID: 10761605] [DOI: 10.1016/S0929-693X(00)88745-X]

[PMID: 3134086] [PMCID: 2546019] [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.296.6635.1504]

[PMID: 15759458]

[PMID: 19467377] [DOI: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.019]

[PMID: 10575159] [DOI: 10.1177/120347549900300605]

[PMID: 7648885]

[PMID: 9186990]