This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Effects of bacteria on their human host

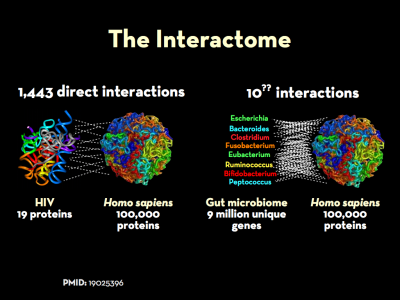

The genomes and the respective proteomes of microbes in the body frequently interact with those expressed by their human hosts. This is a key part of what is know as the interactome. The “massive”1) co-occurrence of protein-coding genes between microbes and humans speaks to the survival advantage of such homology, and the extent to which sequence overlap may play a key role in disease. Indeed, manipulation of host cell fate and orchestrated choreography of inflammatory responses are recurrent themes in the strategies of microbial pathogens.2) Bacteria affect host-cell pathways and human gene expression through a number of increasingly well-documented ways.

It is what bacteria do rather than what they are that commands attention, since our interest centers in the host rather than in the parasite.

Theobald Smith, M.D., circa 1904 3)

Interactome

The genomes and the respective proteomes of microbes in the body frequently interact with those expressed by their human hosts. This is a key part of what is know as the interactome. The “massive”4) co-occurrence of protein-coding genes between microbes and humans speaks to the survival advantage of such homology, and the extent to which sequence overlap may play a key role in disease. Work to understand extent of protein-protein interactions between microbe and man is in its early stages, but there are some indications of its full extent.

Viruses

In a 2007 analysis of sequence similarity between hepatitis C virus (HCV) and humans Kusalik et al. found that pentamers from HCV polyprotein have a widespread and high level of similarity to a large number of human proteins (19,605 human proteins, that is 57.6% of the human proteome).5) Indeed, only a limited number of HCV pentameric fragments have no similarity to the human host. A 2011 study by the same author revised that figure: using once more pentapeptide matching, only 214 motifs – a short sequence pattern of nucleotides in a DNA sequence or amino acids in a protein – out of a total of 3,007 (7.11%) identified HCV as nonself compared to the Homo sapiens proteome.6)

A 2008 study examined thirty viral proteomes were examined for amino acid sequence similarity to the human proteome (as well as a control of 30 sets of human proteins).7) Researchers found that all of the analyzed 30 viral proteomes including human T-lymphotropic virus 1, and Rubella virus had substantial overlap with the human proteome.

Bacteria

Work on bacterial proteomes, while more recent, has also been illuminating. Trost et al. studied in 2010 forty bacterial proteomes for amino acid sequence similarity to the human proteome.8) All bacterial proteomes, were found to share hundreds of nonamer (nine subunit) sequences with the human proteome. The overlap is widespread, with one third of human proteins sharing at least one nonapeptide with one of these bacteria. On the whole, the bacteria-versus-human nonamer overlap is numerically defined by 47,610 total perfect matches disseminated through 10,701 human proteins.

Expanding on this work, Trost et al. performed a pentapeptide and hexapeptide analyses of sequence similarities between bacterial and human DNA.9) He demonstrated that there does not exist a single human protein that does not harbor a bacterial pentapeptide or hexapeptide motif; as the team writes, “not even one.” Interestingly the team found in a 2012 study that while pathogens and nonpathogens had comparable similarity to the human proteome, pathogens causing chronic infections were found to be more similar to the human proteome than those causing acute infections.10) Trost owed this discrepancy to the fact that chronic pathogens are better able to resist immune responses.

Surveys of protein-protein interactions have also been completed for Salmonella,11) 12) Clostridium difficile, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.13)

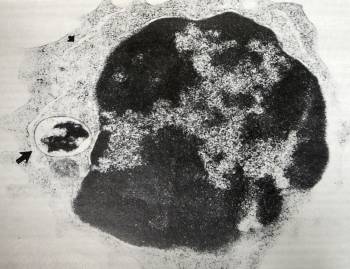

Persistence in phagocytes

The key thing to understand is that a pathogen living in a biofilm A structured community of microorganisms encapsulated within a self-developed protective matrix and living together. outside a cell (for example, a biofilm on a hip joint) can evoke an immune reaction, while a pathogen living inside a nucleated cell can change the way the body works. In particular, an intraphagocytic pathogen can change the way that the immune system works.

Trevor Marshall, PhD

Researchers are increasingly highlighting the intracellular activities of microbes such as Staphylococcus aureus once thought to be exclusively extracellular and what this means for medicine.14)

The Marshall PathogenesisA description for how chronic inflammatory diseases originate and develop. describes how microbes persist intraphagocytically – that is, inside the phagocytes. For example, Enterobacter hormaechei can infect skin cells,15) but where it can really wreak havoc is in infecting the very cells charged with ingesting bacteria. As Kozarov et al. explain, infection of phagocytes by E. hormaechei “can be especially aggravating for an existing inflammationThe complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens or damaged cells. It is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli as well as initiate the healing process for the tissue. as phagocyte recruitment to the site would actually exacerbate the inflammation by delivering additional pathogens.”16) In other words, not only do intraphagocytic microbes remain alive but they have evolved a way to deliver themselves to the site of infection so that they may spread further. Kozarov et al. conclude, “the key step [towards systemic infection] is the persistence of intracellular bacteria in phagocytes.”

Such an adaptation may further account for the resistance of chronic diseases to antibiotic treatment.17) This may explain why several large randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials using antibiotics for the secondary prevention (strategies attempting to diagnose and treat an existing disease in its early stages before it results in significant morbidity) of cardiovascular events have failed to show a benefit.18)

Bacteria affect host-cell pathways

Bacterial pathogens operate by attacking crucial intracellular pathways in their hosts. These pathogens usually target more than one intracellular pathway and often interact at several points in each of these pathways to commandeer them fully.19) These well-documented strategies include, to cite just several among many examples:

- modulation of vesicular traffic, a strategy which provides a protective niche within host cells, including in macrophages and neutrophils, which normally kill bacteria23)

- modulation of membrane traffic as is the case with the Legionnaire's bacterium Legionella pneumophila 24)

- modulation of macrophage cytokineAny of various protein molecules secreted by cells of the immune system that serve to regulate the immune system. production25)

- secretion of proteins, which are similar in effect to substances known to be toxic to humans26)

- creation of virulence factors which suppress MAMPs (Microbial Associated Molecular Patterns)27)

- Ehrlichia/anaplasma (EA) are an obscure group of obligate parasitic intracellular pathogens that intracellularly excrete a substance called host transcriptional protein, which can alter transcription in cell division. Infection with EA may lead to changes in transcription in proliferating cells, and contribute to illnesses such as leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, myelodysplastic disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.28)

- creation of ligands such as Capnine which bind, block, and downregulate the Vitamin D ReceptorA nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response.;29) Alzheimer's may be a case where bacteria stimulate the body's production of the antimicrobial peptide amyloid-beta to dramatically suppress VDRThe Vitamin D Receptor. A nuclear receptor located throughout the body that plays a key role in the innate immune response. activity30)

Bacterial pathogens have used many clever strategies to exploit the interior of host cells to their benefit, by manipulating intracellular trafficking pathways or targeting specific intracellular niches. The challenge facing the cell-mediated immune system is to detect and eliminate these pathogens.

M.S. Glickman and E.G. Pamer 31)

Conversely, harmful bacteria may deregulate genes mediating energy metabolism, and can produce toxins that mutate DNA, affecting the nervous and immune systems. The outcome is various forms of chronic disease, including obesity, diabetes and even cancers.32) 33) 34)

Liping Zhao

Bacteria affect human genes and gene expression

According to one analysis, 463 human genes are changed during an infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis.35) Of the 463 genes whose expression were changed. 366 of them were known genes. The other genes were unknown – mutations. Of the 366 human genes affected, 25 were upregulated and 341 were downregulated. Two more significant effects were the downregulation of the CD14 receptor which was downregulated 2.3-fold, and the VDR receptor which was downregulated 3.3-fold. The mutated genes function in various cellular processes including intracellular signalling, cytoskeletal rearrangement, apoptosis, transcriptional regulation, cell surface receptors, cell-mediated immunity and cellular metabolic pathways.

It is quite plausible that “autoimmunity,” in which it is believed that the body is attacking itself, is caused by bacterial-induced alteration of human genes. All a bacterium would need to do in order to generate an apparent “autoimmuneA condition or disease thought to arise from an overactive immune response of the body against substances and tissues normally present in the body” reaction would be to interfere with the genes necessary for the production of proteins against which autoantibodies are produced.

Pathogenic bacteria have a variety of ways of disrupting the activity of and causing damage to human genes.

- Horizontal gene transferAny process in which a bacterium inserts genetic material into the genomes of other pathogens or into the genome of its host. – Bacteria can insert their DNA into human DNA.

- Interruption of transcription and translation of DNA and RNA – Intracellular pathogens, which inhabit the cytoplasm, can interfere with the steps involved in the transcription and translation processes. Such interference results in genetic mutations, meaning that human DNA is almost certainly altered, over time. The more pathogens people accumulate, the more their genome is potentially altered.

- Disruption of DNA repair mechanisms – Since environmental factors such as exposure to ultraviolet light result in as many as one million individual molecular lesions per cell per day, the potential of intracellular bacteria to interfere with DNA repair mechanisms also greatly interferes with the integrity of the genome and its normal functioning. If the rate of DNA damage exceeds the capacity of the cell to repair it, the accumulation of errors can overwhelm the cell and result in early senescence, apoptosis or cancer. Problems associated with faulty DNA repair functioning result in premature aging, increased sensitivity to carcinogens, and correspondingly increased cancer risk.

Lifelong persistent symbiosis between the human genome and the microbiotaThe bacterial community which causes chronic diseases - one which almost certainly includes multiple species and bacterial forms. [the large community of chronic pathogens that inhabit the human body] must necessarily result in modification of individual genomes. It must necessarily result in the accumulation of ‘junk’ in the cytosol, it must necessarily cause interactions between DNA repair and DNA transcription activity.

Trevor Marshall, PhD

The highly variable range of human genetic mutations induced by bacteria have been identified with some success by researchers with the Human Genome Project. Rather than serving as markers of particular diseases, such mutations generally mark the presence of those pathogens capable of affecting DNA transcription and translation in the nucleus.